[{"predicted_time":"2025-04-28","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-29","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-30","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-01","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-02","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-03","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-04","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-05","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-06","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-07","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-08","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-09","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-10","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-11","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-12","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-13","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-14","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-15","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-16","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-17","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-18","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-19","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-20","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-21","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-22","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-23","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-24","kp":"2"}]

[{"predicted_time":"2025-04-28","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-29","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-30","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-01","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-02","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-03","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-04","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-05","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-06","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-07","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-08","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-09","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-10","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-11","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-12","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-13","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-14","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-15","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-16","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-17","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-18","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-19","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-20","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-21","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-22","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-23","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-05-24","kp":"2"}]

[{"id":"67273","kp":"2.67","predicted_time":"2025-04-29 00:00:00"},{"id":"67276","kp":"2.33","predicted_time":"2025-04-29 03:00:00"},{"id":"67279","kp":"2","predicted_time":"2025-04-29 06:00:00"},{"id":"67282","kp":"2","predicted_time":"2025-04-29 09:00:00"},{"id":"67285","kp":"2","predicted_time":"2025-04-29 12:00:00"},{"id":"67288","kp":"1.67","predicted_time":"2025-04-29 15:00:00"},{"id":"67291","kp":"2.33","predicted_time":"2025-04-29 18:00:00"},{"id":"67294","kp":"2.33","predicted_time":"2025-04-29 21:00:00"},{"id":"67274","kp":"1.67","predicted_time":"2025-04-30 00:00:00"},{"id":"67277","kp":"1.33","predicted_time":"2025-04-30 03:00:00"},{"id":"67280","kp":"1.33","predicted_time":"2025-04-30 06:00:00"},{"id":"67283","kp":"1.33","predicted_time":"2025-04-30 09:00:00"},{"id":"67286","kp":"1.33","predicted_time":"2025-04-30 12:00:00"},{"id":"67289","kp":"1.33","predicted_time":"2025-04-30 15:00:00"},{"id":"67292","kp":"1.67","predicted_time":"2025-04-30 18:00:00"},{"id":"67295","kp":"1.67","predicted_time":"2025-04-30 21:00:00"},{"id":"67275","kp":"1.33","predicted_time":"2025-05-01 00:00:00"},{"id":"67278","kp":"1.33","predicted_time":"2025-05-01 03:00:00"},{"id":"67281","kp":"1.33","predicted_time":"2025-05-01 06:00:00"},{"id":"67284","kp":"1.33","predicted_time":"2025-05-01 09:00:00"},{"id":"67287","kp":"1.67","predicted_time":"2025-05-01 12:00:00"},{"id":"67290","kp":"1.33","predicted_time":"2025-05-01 15:00:00"},{"id":"67293","kp":"1.67","predicted_time":"2025-05-01 18:00:00"},{"id":"67296","kp":"1.67","predicted_time":"2025-05-01 21:00:00"}]

[{"predicted_time":"2024-10-31 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-01 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-02 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-03 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-04 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-05 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-06 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-07 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-08 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-09 01:00:00","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-10 01:00:00","kp":"5.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-11 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-12 01:00:00","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-13 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-14 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-15 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-16 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-17 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-18 01:00:00","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-19 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-20 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-21 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-22 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-23 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-24 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-25 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-26 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-27 01:00:00","kp":"2.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-28 01:00:00","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-29 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-11-30 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-01 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-02 01:00:00","kp":"2.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-03 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-04 01:00:00","kp":"2.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-05 01:00:00","kp":"2.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-06 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-07 01:00:00","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-08 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-09 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-10 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-11 01:00:00","kp":"2.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-12 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-13 01:00:00","kp":"1.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-14 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-15 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-16 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-17 01:00:00","kp":"5.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-18 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-19 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-20 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-21 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-22 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-23 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-24 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-25 01:00:00","kp":"2.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-26 01:00:00","kp":"0.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-27 01:00:00","kp":"1.33"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-28 01:00:00","kp":"1.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-29 01:00:00","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-30 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2024-12-31 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-01 01:00:00","kp":"8"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-02 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-03 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-04 01:00:00","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-05 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-06 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-07 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-08 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-09 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-10 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-11 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-12 01:00:00","kp":"2.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-13 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-14 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-15 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-16 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-17 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-18 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-19 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-20 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-21 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-22 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-23 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-24 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-25 01:00:00","kp":"1.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-26 01:00:00","kp":"1"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-27 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-28 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-29 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-30 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-01-31 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-01 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-02 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-03 01:00:00","kp":"1.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-04 01:00:00","kp":"1.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-05 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-06 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-07 01:00:00","kp":"1.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-08 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-09 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-10 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-11 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-12 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-13 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-14 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-15 01:00:00","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-16 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-17 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-18 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-19 01:00:00","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-20 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-21 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-22 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-23 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-24 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-25 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-26 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-27 01:00:00","kp":"5.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-02-28 01:00:00","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-01 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-02 01:00:00","kp":"2.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-03 01:00:00","kp":"1.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-04 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-05 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-06 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-07 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-08 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-09 01:00:00","kp":"5.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-10 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-11 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-12 01:00:00","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-13 01:00:00","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-14 01:00:00","kp":"5.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-15 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-16 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-17 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-18 01:00:00","kp":"3.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-19 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-20 01:00:00","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-21 01:00:00","kp":"5.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-22 01:00:00","kp":"5.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-23 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-24 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-25 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-26 01:00:00","kp":"6.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-27 01:00:00","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-28 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-29 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-30 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-03-31 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-01 01:00:00","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-02 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-03 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-04 01:00:00","kp":"5.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-05 01:00:00","kp":"5.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-06 01:00:00","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-07 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-08 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-09 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-10 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-11 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-12 01:00:00","kp":"4.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-13 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-14 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-15 01:00:00","kp":"6.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-16 01:00:00","kp":"7.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-17 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-18 01:00:00","kp":"4"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-19 01:00:00","kp":"4.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-20 01:00:00","kp":"5"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-21 01:00:00","kp":"5.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-22 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-23 01:00:00","kp":"3"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-24 01:00:00","kp":"3.67"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-25 01:00:00","kp":"2"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-26 01:00:00","kp":"2.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-27 01:00:00","kp":"2.33"},{"predicted_time":"2025-04-28 01:00:00","kp":"2.67"}]

Aurora Forecast

You are viewing 3-Day Forecast data in Alaska time.

Time Zone:

N. America

Europe

N. Pole

S. Pole

Alaska

Time Zone:

3-Day Forecast

Time (UTC)

27-Day Forecast

Date

Historical Data

Date

Live Cameras

Live Cameras

Current Activity

Watch the last few seconds of the animation to see what is predicted over your location in the next 30 minutes.

Source: Space Weather Prediction Center

Viewing the Aurora

- How often can I see aurora?

-

There is always some aurora at some place on Earth; however, the sky must be dark and at least partially clear in order for the aurora to be visible. When the flow of particles known as the solar wind is calm, the aurora might only be occurring at very high latitudes and appear faint, but nevertheless, there is still aurora. Sunlight and clouds are the biggest obstacles to observing this elusive phenomenon.

- Where is the best place to see aurora?

-

The best places to view aurora are high northern latitudes during the winter in northern Europe, Asia and North America.

To see the aurora you need a mostly clear and dark sky. During very large auroral events, the aurora may be seen at lower latitudes throughout the world, but these are rare. During an extreme event in May 2024, the aurora borealis was visible as far south as India, Morocco and Mexico and the aurora australis as far north as Perth, Australia, Argentina, and Namibia.

During average activity levels, auroral displays will be overhead at high northern or southern latitudes. Places like Fairbanks, Alaska; Dawson City, Yukon; Yellowknife, NWT; Churchill, Manitoba; the southern tip of Greenland; Reykjavik, Iceland; Tromsø, Norway; and the northern coast of Siberia all offer a good chance to view the aurora overhead.

At lower latitudes, you might be able to see aurora on the northern horizon when activity picks up a little. In the southern hemisphere, the aurora has to be fairly active before it can be seen from places other than Antarctica. Hobart, Tasmania and the southern tip of New Zealand have about the same chance of seeing aurora as Vancouver, B.C., South Dakota, Michigan, Scotland, or St. Petersburg, Russia. Fairly strong auroral activity is required for aurora viewing in those locations.

- What is the best time of day to see aurora?

-

Although aurora occurs throughout the night, the best time to watch for the aurora is the three or four hours centered around midnight. Active auroral displays tend to be more diffuse and fragmented later in the night, which means that 9 p.m. to 3 a.m. is typically the time period with higher probability of seeing spectacular auroral displays over interior Alaska in winter. Since clear sky and darkness are both essential to see aurora, the best time is determined by the weather and by the sunrise and sunset times.

Moonlight may also affect aurora viewing. When the moon is full or close to full, the added ambient light may prevent you from seeing dim auroral features. However, this same effect also may enhance their colors. The bright moon activates more color and detail-sensitive cone cells in your eyes. In contrast, rods are photoreceptor cells that work well in the dark, but only produce images in black and white and with low levels of detail. Moonlight provides cone cells with the right amount of light to “turn on” so you can see colors in the aurora. When the aurora becomes very bright, even with no moon you may see colors in the aurora. For photography enthusiasts, third-quarter or new moon phases are best. The aurora in the sky can shine on the ground and produce interesting reflections that get “washed out” when the moon is more full. Note: In the Arctic, the first-quarter moon does not set below the horizon, while the third-quarter moon does not rise.

- What time of year is best for seeing aurora?

-

Partially clear skies are a requirement (the clearer the sky, the more aurora that can be seen), so you should try to choose a location and a season that has the clearest skies. Statistically, the continental locations in Russia, Alaska and western Canada under the auroral zone have the clearest skies, and in the spring, the skies of Iceland and Scandinavia are usually clear. Furthermore, there is a quite strong (but poorly understood) tendency for auroral activity to be more intense around fall and spring equinox compared to summer and winter solstice known as the “Russell-McPherron effect.” This means that the statistical likelihood of seeing aurora over Interior Alaska is roughly twice as high on the equinox as it is at solstice. With these factors combined, aurora viewing may be best in locations with clear skies and around the spring (March) or fall (September) equinox.

Sunlight prevents viewing the aurora during the summer at high latitudes. The skies at night are simply too bright as the sun climbs in the sky until the June 21 solstice and then descends. (If active, aurora can generally be seen after civil twilight. See day length in your viewing location). Here in Fairbanks, at about latitude 64.8, our aurora viewing “season” is roughly August 21 to April 21. The odds are in your favor between those dates: if the weather is clear and you stay for at least three nights, it’s highly likely (though never certain!) that you will see the aurora. Although the sun does set to varying degrees in Fairbanks between April 22 and August 20, the sky doesn’t get dark enough to see the aurora even if it was a spectacular display.

Note: There are two “shoulder seasons,” one for some time after April 21 and the other for some time before August 20, where the skies are dark enough to potentially see aurora for very brief periods of time during twilight. However, when scheduling your aurora viewing travel, we recommend avoiding these shoulder seasons and visiting between August 21 and April 21.

- Why are some years better than others to view the aurora?

-

The number of sunspots on the sun's surface changes on a fairly regular cycle, which scientists refer to as the sun's 11-year cycle variation. Sunspot activity tends to peak every 11 years. This peak is called the solar maximum. The last solar maximum was in 2014; the next is expected in winter 2024-25. Auroral activity tends to peak slightly after the solar maximum by around one year. Like the transitions between summer and winter seasons on Earth, the sun’s activity cycle takes time to ascend to solar maximum and decline to solar minimum. Although the chances of seeing the aurora at lower latitudes increase when the sunspot cycle is at a maximum, aurora viewing at higher latitudes is not as dependent on the solar maximum because the auroral oval is normally present.

- Where should I view the aurora when I'm in Fairbanks, Alaska?

-

For specific information on accommodations, tour companies, etc., we suggest www.explorefairbanks.com.

People who live in Fairbanks are accustomed to spectacular views of the aurora borealis. Many residents routinely stay up late to photograph this phenomenon or simply to experience the widely different forms it takes with each new display. Some people view the aurora from their homes, but many travel away from the city lights for the most spectacular views.

Visitors to Fairbanks should plan to watch from a hill away from city lights with a clear view of the horizon, since the aurora can occur in any part of the sky. During solar activity maximum years, many auroral substorms start south of Fairbanks. During years of minimum solar activity, many auroral substorms start north of Fairbanks and occur in the midnight hours.

Although trees make good foreground subjects in auroral photographs, too many of them can limit the full experience of the aurora, so photographers may want to search out a location with a clear view of the northern horizon. Another concern for visitors is the extremely cold winter weather. In those conditions, small problems may become disasters in remote areas. If you are aurora hunting at cold temperatures, please be prepared! Visit this page for tips on safely enjoying the winter season.

Recommended aurora viewing sites around Fairbanks include:

- Chena Lakes Recreation Area

- Tanana Lakes Recreation Area, just south of Fairbanks

- Cleary Summit

- Ester, Wickersham and Murphy Domes

- Haystack Mountain on the Elliot Highway

- Some turnouts along the Elliot, Steese and Parks Highways and Chena Hot Springs Road

- Some turnouts along Nordale Road

- Ballaine Road turnout near the Goldstream Creek bridge

- Visit the Explore Fairbanks Winter Guide

Science of the Aurora

- What is the aurora?

-

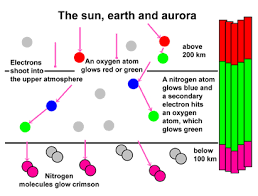

The aurora is a luminous glow frequently seen around the geomagnetic poles of the northern (aurora borealis) and southern (aurora australis) hemispheres. The light is caused by collisions between electrically charged particles streaming from outer space that enter Earth’s atmosphere and collide with molecules and atoms of gas (primarily oxygen and nitrogen). When the electrons and protons from the sun collide with gases in the Earth’s atmosphere, the atmospheric particles (or gases) gain energy. To return to their normal state, they release that energy in the form of light. The principle is similar to what happens in a neon light: electricity runs through the light fixture to excite the neon gas inside, and when the neon is excited, it gives off a brilliant light.

The dancing lights of the aurora are seen around the magnetic poles of the northern and southern hemispheres because the electrons from the sun travel along magnetic field lines in the Earth’s magnetosphere. The magnetosphere is the extension of Earth’s magnetic field into a vast, comet-shaped bubble around our planet that acts as a sort of protective shield against space weather. The magnetosphere works to deflect and funnel particles from the solar wind into the space environment surrounding our planet. The “weak points” of our protective magnetic shield are over the poles where field lines converge. Many particles end up funneled over these areas with some penetrating into the upper atmosphere and colliding with other atoms or molecules to produce aurora light.

- What is the auroral oval?

-

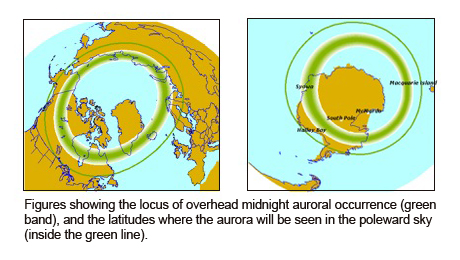

The two figures below show the locations with the most frequent occurrences of aurora borealis (left) and aurora australis (right) during the period of best viewing around the middle of the night. The “quiet” state of the aurora is on average a thin oval band situated around 67-68 degrees in geomagnetic latitude. Under quiet solar wind conditions, the aurora will most likely occur inside the region shown with the auroral oval, and if you travel to these regions during dark and clear conditions and stay for 3-7 days, you will most likely see the aurora. These auroral ovals can expand when geomagnetic activity is enhanced, bringing sightings of aurora to lower latitudes. This three-day forecast and many other sites, including the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC), rely on the Kp index as an indicator of the auroral oval size. Inside the auroral oval, however, Kp is less relevant, since even when global activity is low, auroral activity can be high.

- What makes the colors of the aurora?

-

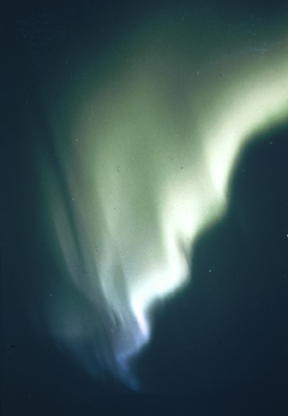

The composition and density of the atmosphere and the altitude of the collisions determine the colors. The aurora is most often seen as a striking green, but it also occasionally shows off other colors, ranging from red to pink or blue to purple. Oxygen at about 60 miles up gives off the familiar green-yellow color, while oxygen at higher altitudes (about 200 miles above Earth’s surface) gives all-red auroras. Nitrogen in different forms produces the blue light. Purple occurs when nitrogen at higher altitudes mixes with the red auroral emissions from oxygen. Within a small layer between the red and green aurora, it is possible to even see orange!

Cameras have different sensitivities to colors than the human eye; therefore, there is often more red aurora in photos than you can see with the unaided eye. Just like sunlight, which appears to be white, is a blend of the colors of the rainbow, the aurora is also a mixture of colors. The overall impression is a greenish-whitish glow. Since there is more oxygen at high altitudes, the red aurora tends to be on top of the regular green aurora. Very intense aurora often has a purple rim at the bottom. The purple results from a mixture of blue and red emissions from nitrogen molecules.

- What is the altitude of the aurora?

-

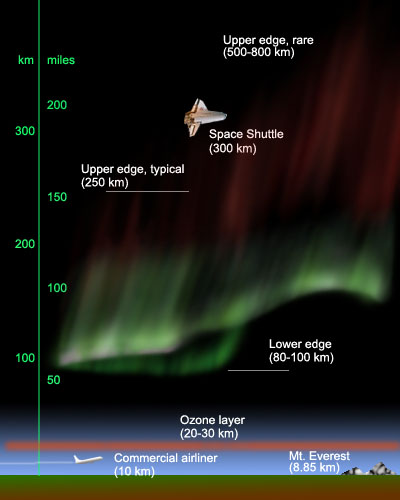

The bottom edge of the aurora is typically about 60 miles (100 kilometers) above the surface of the Earth. The top of the visible aurora peters out at about 120 to 200 miles (200 to 300 kilometers), but sometimes aurora can be seen as high as 500 miles (800 kilometers).

Viewing angle also impacts what one sees when aurora gazing; see the image below (courtesy of Aurorasaurus).

- What are the types of aurora?

-

Auroral forms can be divided into broad categories based on activity level and the viewer's perspective.

Homogeneous arc

At its least active, the auroral curtain forms diffuse, glowing streaks hanging quietly in the sky. This form has no distinct structure.

Rayed arc

When the aurora becomes slightly more active, vertical stripes or striations, called rays, form. These are actually fine pleats in the auroral curtain.

Rising vapor column

The auroral curtain sometimes appears to touch a distant mountain top or even rise like smoke. This illusion occurs because you are seeing a several-hundred mile long aurora near the horizon where perspective gives the illusion that it is touching the ground.

Corona

The aurora may appear as rays shooting out in all directions from a single point in the sky. This dramatic form occurs when you are directly beneath the swirls and folds of an active curtain. The rays are actually hundreds of miles long and perspective makes them appear to converge.

- Can you hear the aurora?

-

The best answer is “Maybe.” It is easy to say that the aurora makes no audible sound. The upper atmosphere is too thin to carry sound waves, and the aurora is so far away that it would take a sound wave five minutes to travel from an overhead aurora to the ground. But many people claim that they hear something at the same time when there is aurora in the sky. We are aware of only one case where a microphone has been able to detect audible sound associated with aurora (visit Auroral Acoustics: the web site does not have sound samples, but you'll find a link to an in-depth paper and recent news on this topic). The sound is often described as whistling, hissing, bristling or swooshing. Some even describe it like sizzling bacon on a pan. What gives people the sensation of hearing sound during auroral displays is an unanswered question. By searching for an answer to that question, we will probably learn more about the brain and how sensory perception works than about the aurora.

- Can you predict when and where there will be aurora?

-

Scientists can predict when and where there will be aurora, but with less confidence than they can predict the regular weather.

The ultimate energy source for the aurora is the solar wind. When the solar wind is calm, there tends to be minimal aurora; when the solar wind is strong and perturbed, there is a chance of intense aurora. The sun turns on its own axis once every 27 days, so an active region that produced perturbations which resulted in aurora might again cause aurora 27 days later. The solar wind takes approximately three days to get to the Earth on its way from the sun. Observing the sun and predicting perturbations in the solar wind resulting from events taking place on the sun (such as flares or coronal mass ejections) provides information in a few days in advance of possible auroral displays. Spacecraft such as the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) and Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) provide researchers with data on activity occurring on the surface of the sun as well as in the solar magnetic field.

Another source of data used to predict the aurora comes from satellites located approximately 90 minutes or 1,500,000 km away from Earth. The Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) and Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) Real-Time Solar Wind satellites provide real-time data to researchers about geomagnetic storms. Data from these satellites provide about one to two hours warning of conditions that may cause enhanced auroral displays.

- What is the solar wind?

-

Streams of charged particles that produce the aurora come from the corona, the outermost layer of the sun's atmosphere. The corona is exceedingly hot, measuring more than two million degrees Fahrenheit. The high temperature causes hydrogen atoms to split into protons and electrons, and the resulting gas of charged particles is called plasma, which is electrically conductive. The solar plasma is so hot that it breaks free of the sun's gravitational force and blows away from the surface in all directions. The movement of this plasma is called solar wind. The intensity of the solar wind and the magnetic field carried by it change constantly. When the solar wind blows more strongly, we see more active and brighter aurora on Earth.

- What are Kp numbers?

-

The Kp number is a numeric scale that describes geomagnetic activity. The number is computed by averaging the magnetic activity from around eight stations around the world every three hours. The metric ranges from 0 to 9 (with 0 being calm, 1 very weak, and all the way up to 9, which would represent an extreme geomagnetic storm). On average, there are only one or two extreme geomagnetic storms per solar cycle (~11 years). Anything above a Kp 5 is classified as a geomagnetic storm.

The Kp index was introduced by a German scientist named Julius Bartels in 1939. The abbreviation Kp comes from the German "Kennziffer Planetarische," which translates loosely as “planetary index number,” although it is better known in English as simply the planetary index, and is usually designated as Kp (number from 0-9).

Can the Kp forecast the aurora in Fairbanks? Yes and no. Kp index is derived from 3-hour averages of observations from equatorial magnetometer stations to characterize global magnetic activity. When global geomagnetic activity is higher, the likelihood of seeing aurora increases globally. However, local conditions could be quite different from global activity. That's why scientists divide geomagnetic activity into two categories: geomagnetic storms and substorms. Auroral phenomena are more closely related to substorms, which are used to define the almost nightly occurrences of auroral activity. Aurora chasers use local magnetometer measurements (like our GIMA chain), aurora cameras (like our Poker Flat DASC; see under “Live Cameras” on this page), models like OVATION, or reports from social media or sites like Aurorasaurus for more accurate, real-time information.

Forecasting the Aurora

- What's happening now?

-

Magnetometers provide a quantitative view of the level of geomagnetic disturbance occurring. A sudden steep change (i.e., tens or hundreds of nanotesla) in the magnetometer data is usually an indicator that an extended period (0.5 hours or more) of active aurora is beginning. This is especially true just before midnight. Scientists also find it helpful to see the time history of the magnetometer trace, since other indicators, like the all-sky camera, only show current conditions.

Visit the magnetometer monitor for a chart of the current conditions, and view the all-sky camera at Poker Flat Research Range (65.13° N, 147.49° W) to see aurora occurring northeast of Fairbanks, Alaska. The Poker Flat camera and others are linked on this page under the “Live Cameras” section.

- 1-hour Forecast

-

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) OVATION is updated every 5 minutes. The animation shows auroral activity that occurred over the Northern Hemisphere in the last 24 hours. The animation is in Coordinated Universal Time (UTC); fast forward to the last few seconds of the animation to see what is predicted for the next 30 minutes. The model depicts a day/night terminator showing what areas of the world are sunlit and what areas are in darkness. Auroras cannot be seen during the daytime.

- 3-day Forecast

-

Remote sensing spacecraft monitor the sun for indications of eruptions that eject solar material towards the Earth, or regions where continuous high-speed streams of material are escaping and heading earthward. In either case, the travel time to Earth for such material leaving the sun is 1 to 3 days. This allows relatively accurate forecasts to be made on these look-ahead time scales.

- 27-day Forecast

-

Just as Earth rotates on its axis and makes a complete rotation every 24 hours, the sun spins on an axis and makes one complete rotation every ~27 days. Coronal holes on the sun allow solar material to flow out at high speeds. When these holes on the sun are facing Earth, we may experience enhanced auroral displays, among other effects. As the sun rotates, these coronal holes and other active regions result in high-speed streams of plasma that are likely to reoccur every 27 days until the phenomena dissipate; therefore, if there is high auroral activity today, it’s possible that there will be high auroral activity again in 27 days. This 27-day period is known as the Carrington Rotation.