A brand new world in the Aleutians

In a science report in which they wrapped up their 2008 field season, biologists Ray Buchheit and Chris Ford wrote, under a section titled Interesting Observations, “Our island blew up.”

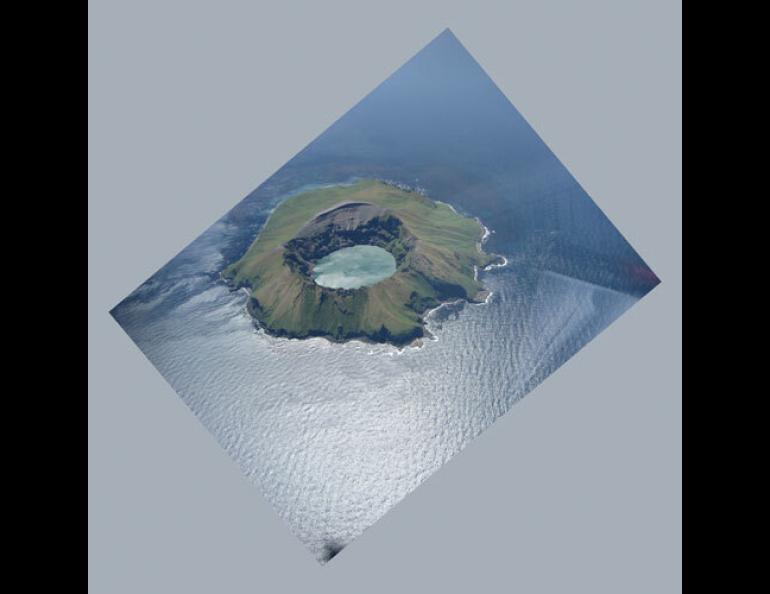

Their island was Kasatochi, a 700-acre green island in the mid-Aleutians that featured an old fox trapper’s cabin and a crater filled with aquamarine water.

“It looked like Monster Island,” a volcanologist said. “You were expecting Godzilla to stomp around the corner any minute.”

That was the old Kasatochi, the one before an eruption on Aug. 7, 2008. Today’s Kasatochi, now 32 percent larger, probably has no crested or least auklets, down from about 200,000 a year ago. After the eruption, there were probably no insects or plants on the island either. There is also no evidence of the cabin Buchheit and Ford were living in when they felt earthquakes that lasted for nine minutes, until a fishing boat captain plucked them from the island with one bag each. One hour later, Kasatochi erupted for the first time in recorded history.

The eruption blew an ash cloud 45,000 feet into the air, put more sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere than any volcano since Pinatubo in 1991, cancelled 44 Alaska Airlines flights, and scattered light into great sunsets from Belgium to Salt Lake City, Utah.

One year after an eruption that destroyed and rebuilt an Aleutian Island, scientists are returning to see what happens at Ground Zero after an explosive eruptions. Will the birds be back? What about insects? Plants?

I’ll be heading to the island this week with a group of scientists from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, the University of Alaska, and the Alaska Volcano Observatory. Among them will be Chris Nye of the Alaska Volcano Observatory, there to document geological changes in the island; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service botanist Steve Talbot, who will see what, if any, plants have returned to the island; Steve Jewett, a UAF diver and ecologist, who will follow up on reports by divers in June that showed almost no marine life down to about 30 feet below the new shoreline of Kasatochi; and Derek Sikes, the curator of insects at the University of Alaska Museum of the North, who was there before the eruption.

Sikes will look for insects that have wafted over on the wind and often kickstart the recolonization of the island.

“Other studies have found that these arthropods dispersing to these barren sites and expiring add considerable nutrients and enable a predator/scavenger community to develop before the herbivore community,” Sikes wrote in an e-mail.

On a visit to the island in June, biologist Jeff Williams of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge said that auklets had returned to the island, but its new ashen surface was not good for birds accustomed to nesting on rocky cliffs.

“There were hundreds of thousands of auklets about in June but they had nowhere to go,” Williams wrote in an e-mail he sent from Adak. “I think they will be gone by the time you are there, so be prepared for a very sterile looking environment.

“We expect Kasatochi to be quite barren with no signs yet of recovery this year,” wrote Williams. “We expect to document a lot of zeroes.”

I’m psyched to walk on the ash of this strange, new world. Next week, I’ll write about what is found, or isn’t, on Kasatochi, the island that blew up.