Cosmic Rays: Deadly Hazard or Boon to Science?

Nationally syndicated columnist L. M. Boyd recently posed a question to his readers: "A cosmic ray hits you about once a minute. Feel anything?" It must have made a lot of people wonder what he was talking about.

Cosmic rays wander about willy-nilly at tremendous speeds over the universe. In the vicinity of the earth, most have been emitted by the sun during solar flares, and, while they present a threat to unprotected astronauts, the atmosphere renders most of them harmless before they reach the ground. The "rays" are actually ions, the heavy central portions of atoms that have been stripped of an outer layer of orbiting electrons. One of the most common is the iron nucleus.

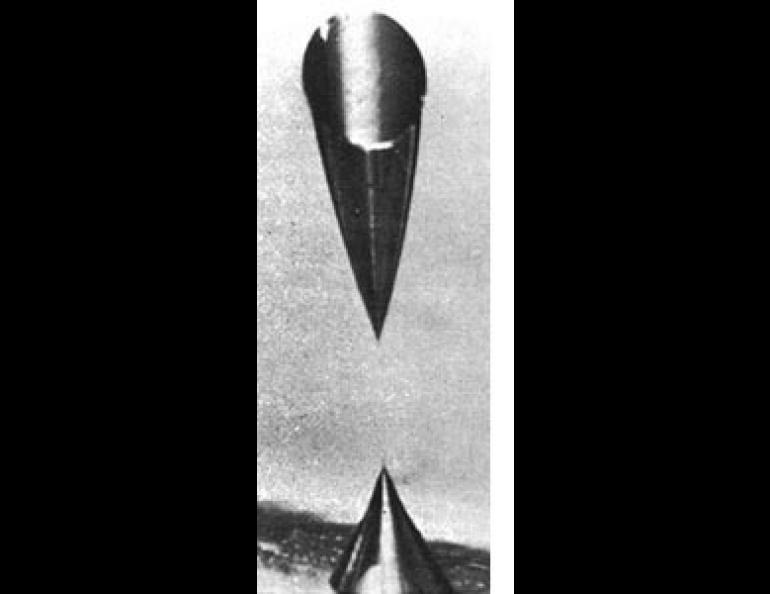

They will penetrate just about anything, and will do a certain amount of damage when they do. Fortunately, the dosage is small and we heal quickly after we're hit, but most inorganic materials don't heal. In other words, a "bullet track" of disturbed molecular structure is left along the path that the cosmic ray has taken. In recent years, scientists have found that this path-forming phenomenon can be used to date materials as diverse as relatively recent pottery fragments or rocks billions of years old. Taking the assumption that the influx of cosmic rays occurs at a more or less constant rate, a mere count of the tracks should give an estimate of how long the material has been exposed. The method has been shown to be accurate in dating artifacts such as spearheads and ancient lava flows, where the ages can be checked by other means.

The method is fairly simple A "thin section" is made of a slice of the material to be examined. This is a slice about a millimeter thick (half the thickness of a pencil lead). The surfaces are then etched with a powerful acid. The acid will erode the material away faster along the damaged paths that the cosmic particle has taken, and the paths will show up clearly under an electron microscope. The tracks can then be easily counted. Cosmic ray detectors made of thin mica or plastic sheets are routinely carried aboard space flights.

The method can also be used to date rocks that have never been exposed to cosmic rays at the earth's surface. In this case, the paths are fission tracks caused by the particles released during spontaneous decay of uranium in the rock. Knowing the uranium content of the rock and the rate at which it decays, a count of the fission tracks produced during the time since the rock has cooled gives a precise measure of its age.

Fission tracks are used not only for geologic mapping, but for such diverse studies as measurements of sediment accumulation on the ocean floors and the history of meteorites. By strapping cosmic ray counters to the back of birds, biologists are even able to use the technique to study features of the birds' migratory habits. The incoming particles travel further along the collecting sample at higher altitudes because there is less interference by the atmosphere. One rather unsurprising finding has been that birds fly higher when the weather is good.