Diversity helps a place survive

Last week, I wrote about some of the breaks the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks has enjoyed during its 75-year existence.

Another key for this place where a few dozen researchers study things “from the center of the Earth to the center of the sun” is that its directors have followed the advice of your financial advisor: diversify your portfolio.

The Geophysical Institute hatched in the late 1940s because the aurora sometimes interfered with high-frequency radio communications used by ship captains and aircraft pilots during World War II.

The fledgling institute and its graduate students who became experts in space physics were then in a good place during the International Geophysical Year of 1957-1958. During that vast campaign, there was plenty of funded work to do, with new instruments that had to be tweaked for use in the far north. And someone — those institute students — also had to make sense of the thousands of black-and-white aurora images those all-sky cameras provided.

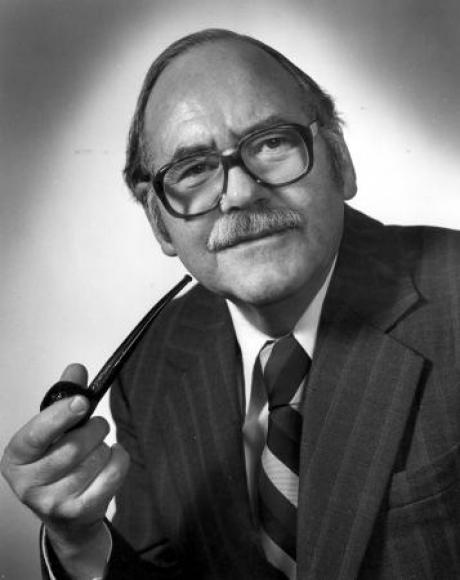

Australian Keith Mather, a physicist who became director of the institute in 1963, was happy to govern the team of respected and successful aurora experts here in Fairbanks. But he also knew that to survive over the long term, the place had to become something more.

During “the post-war euphoria for science and relatively plentiful funding,” Mather swung the doors open to those who studied things other than the thin air 60 miles above our heads. One of the first to walk in was former Minnesotan Carl Benson, who will tell you he was one of the first here for whom the ground was “not just for bolting instruments into.”

Benson, at 94 still a good-humored presence in these halls, was a favorite of Mather’s for his Midwest charm, and because Benson dove into the studies of many northern phenomena such as ice fog, which forms in Fairbanks when the air is colder than about minus 30 Fahrenheit and water vapor floats in the air like cotton candy. Benson also worked on glaciers in the Brooks Range and Wrangell Mountains, which included building a “volcanically heated hut” on Mt. Wrangell’s summit.

One year after Mather became director, the 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake rocked the world. Mather recognized that geophysical event as an opportunity. The institute had recently started a seismology section, which expanded rapidly due to the interest a magnitude 9.2 earthquake stimulates.

Other scientists attracted here would soon write their own grant proposals for studying volcanoes (dozens of which in Alaska have been active in historic times), and atmospheric science (such as the study of a blob of pollution known as Arctic Haze, which visited Alaska each spring from northern Russia and Asia).

The opportunities kept coming, like the construction of a rocket range in the muskeg 30 miles of Fairbanks, and the building of ground-based receiving stations for information gathered by polar-orbiting satellites that loop directly over Fairbanks. The institute is now also a far-northern base station for unmanned aerial vehicles and their pilots.

People still study the aurora and other aspects of space physics here, but you are just as likely to run into a grad student who squints at satellite images of the Seward Peninsula and counts beaver dams.

One of those graduate students way back at the beginning was Syun-Ichi Akasofu, who turned 90 last December and still lives in Fairbanks. Not long after he arrived in the far north from Japan, Akasofu — later a director of the institute himself — saw how Mather’s efforts to diversify gave this place wings.

“Keith’s directorship made the caterpillar institute into a butterfly institute,” he said.