Formation Flying makes Migration Less of a Drag

Uh oh. It's that time again, when distant, throaty honks cause Alaskans to look skyward. Migrating geese, cranes and ducks signal the end of summer as they fly in a V-shaped wedge toward warm places, like a spear being hurled out of Alaska. A physics question comes to mind amid the melancholy reflections the snow birds inspire: Why do the birds fly in formation?

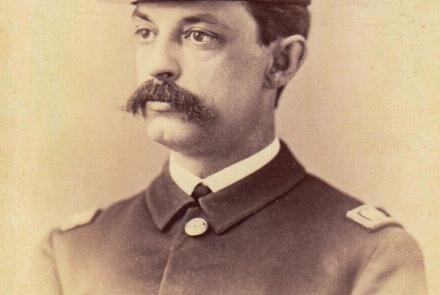

Larry Gedney, a former associate professor of geophysics at the Geophysical Institute who died in 1992, explored the question in this column more than a decade ago. Gedney was told as a boy that father goose was at the head of the V-formation with his family spread out behind. Another theory is that the lead goose is breaking trail for his flock-mates, much like a front-running bicycle racer allows teammates to decrease wind resistance by drafting directly behind. When the lead goose gets pooped, he supposedly gives a honk and another takes his place at the tip of the V.

A conflicting theory presented in an article in Science, says that in a proper V all birds experience approximately the same amount of benefit from their neighbors. Although it doesn't seem plausible, the theory suggests that even the leader at the tip of the formation benefits from the wind currents produced by the birds directly behind it.

Pilots know the migrating birds' mechanism as the "wing tip vortex." The volume of air surrounding a bird must always remain the same, so when a bird displaces air downward on a wing beat, some air also must be displaced upward. This upward displacement of air creates an upwash beyond a bird's wing tips that enables the bird beside or behind it to fly with a bit less energy, like a hang-glider who catches an updraft of warm air.

Because the upwash is produced off a bird's wing tips, it might seem advantageous for birds to fly shoulder-to-shoulder like the offensive line of a football team. But, according to the Science article, such a formation would force the birds on the outside of the formation to work a lot harder than those flanked by birds on each side. Those with neighbors at both wing tips would enjoy twice the lift of those on the end of the line. The V-formation ensures that some birds don't end up looking like bodybuilders while others cruise along in their wake.

The energy efficiency of the V-formation was pointed out in the Science article. Researchers discovered that a flock of 25 birds in formation can fly 70 percent farther than a single bird using the same amount of energy.

Stragglers who bust out of the V pay a price in increased air friction and a higher energy cost. For this reason, the system is self-stabilizing--even young birds who haven't migrated before quickly feel the advantages of flying in the V.

Birds rarely make a perfect V in their migrations, but even a formation that looks like a large check mark is effective. The V-formation works as an energy-saver so long as the lead bird, at the apex of the V, has birds on both sides.

A lazy bird who decides he wants to tuck inside the V will save energy, but he will do nothing to enhance the flight efficiency of the flock. Apparently, birds won't stand for malingerers in the flock, or we'd see more birds flying in the middle of the formation.

The researchers who presented the Science study in 1970 also found that single birds in migration fly 24 percent faster than a cruising flock of the same species. Gedney suggested the stragglers are frantically trying to make their way back to a flock in formation, where teamwork makes the yearly task of migration less of a drag.