Moose flies a high-summer Alaska pest

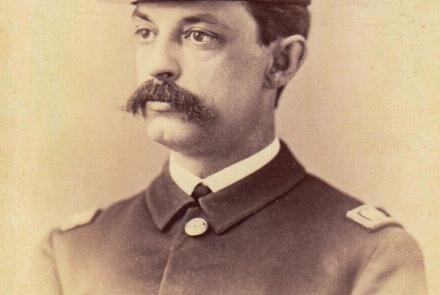

While boating down the Yukon River during the hottest summer recorded in Alaska (1915, when Fort Yukon reached 100 degrees Fahrenheit), missionary Hudson Stuck wrote about the wildlife that most bothered his party.

“With the failure of a little breeze and the overcasting of the sky, the weather grows oppressively sultry and a swarm of horse-flies, or moose-flies as they are called in these parts, makes appearance — large venomous insects that bite a piece out of one’s flesh when they alight.”

A century later, the helmeted flies almost the size of a moose nugget maintain a healthy presence along Alaska’s waterways. The flies from the family Tabanidae (called horse and deer flies in other places) drive moose to gallops of terror. The big flies seek mammals, including you, for meals of blood that allow them to produce more flies.

The creatures are stout enough to absorb the smack of a palm and then fly away. With evolved stealth, they feather-land on skin. Soon after, the victim feels the pierce of a needle many times worse than a mosquito bite. Horse and deer-fly expert James Goodwin of Jarvis Christian College in Texas explains: “The female’s mouthparts include two pairs of cutting blades,” he wrote in an email. “A female literally chews or cuts through the skin with these blades, creating a wound that serves as a pool which fills up with blood.”

If left unmolested — which almost never happens when a fly slices a human — the fly laps blood until its abdomen is about to burst. Biologist J.L. Webb, on assignment to study horse flies in California and Nevada in the 1920s, pulled out his stopwatch when he witnessed a fly on a “perfectly calm” cow. “The fly fed to apparent satiety in 11 minutes and 10 seconds,” Webb reported.

As is the case with mosquitoes and other biting flies that have prevented humans from overpopulating Alaska, the females are the ones to fear. The adult males have no flesh-cutting apparatus, surviving on a diet of nectar and pollen. From an evolutionary perspective it’s hard to fault the females in their quest for protein-rich meals. We are warm, slow-moving and contain the nectar of life.

Sensors on the flies’ large heads detect the carbon dioxide we emit and the heat of our bodies, along with our clothing and silhouettes and other features that make us stand out from the alder bushes. Their multicolored compound eyes sometimes feature bold stripes, which may be how males and females of the same species recognize one another.

Thirty to 40 different species of the giant flies buzz the air of Alaska, some of them the same type that harass cattle and horses in Texas. The winged adults only live three or four weeks here, just as they do down south. Entomologists have found the big flies everywhere on the planet except Hawaii, Greenland and Iceland.

And, while everyone in more southern places calls them horse flies, Hudson Stuck wrote that moose fly is a much better fit for the Alaska version.

“Here we are annoyed by them almost beyond endurance,” he wrote on his sweltering river trip of a century ago. “And not a horse within 100 miles.”

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute. A version of this column appeared in 2012.