"Ringstreaked, Speckled, and Spotted"

"I will pass through all thy flock to day, removing from thence all the speckled and spotted cattle, and all the brown cattle among the sheep, and the spotted and speckled among the goats: and of such shall be my hire."

-- Genesis 31: 32

The first step in science, the one on which all the experiments are based, is simply playing with ideas. Granted, we don't usually publish this part of the scientific process, but both Larry and Neil have done it here in the past and that's what I'm going to do today. The topic? Why is white spotting so common in domesticated animals, and so rare in wild ones?

White markings do occur in wild animals -- white tails on deer and rabbits, white face markings in wolves, stripes on zebras, chest patches on mink, and warning white bands on skunks. But these markings are very consistent in location from animal to animal within a species, and they serve a purpose -- communication, breaking up the animal's outline, or warning potential predators. The variable blazes, stockings, white toes, chest patches, collars, and tail tips we see in some breeds of almost every domesticated mammal are extremely rare in wild mammals. (The "wild" horses of the west, which do have a wide array of white markings, are in fact feral, that is, descended from domesticated ancestors.)

So we really have two questions: why aren't white markings of the domesticated type seen in wild mammals, and why are they common in domestic stock?

One obvious answer to the first question in that white markings, at least for most of the year, make an animal more conspicuous to potential predators or prey. The persistence of white markings in feral horse herds argues against this being the only factor involved.

Many genes producing white markings or all-white animals also affect the animal in other ways, producing anemia, nervous system problems, or sterility. These genes would tend to die out rapidly in the wild.

Another possibility is color prejudice among wild animals. This isn't quite as crazy as it sounds; possibly the biggest difference between domesticated and wild animals is that domestic animals have been selected to breed very freely, while wild animals of both sexes (as witnessed by the frustration of zoos trying to breed them in captivity) are extremely choosy about their mates. Some insects and birds will refuse to breed with a potential mate whose color or markings are not "right" for the species; if mammals react the same way, the occasional piebald moose or white-spotted wolf probably never finds a mate to help pass on the genes for spotting.

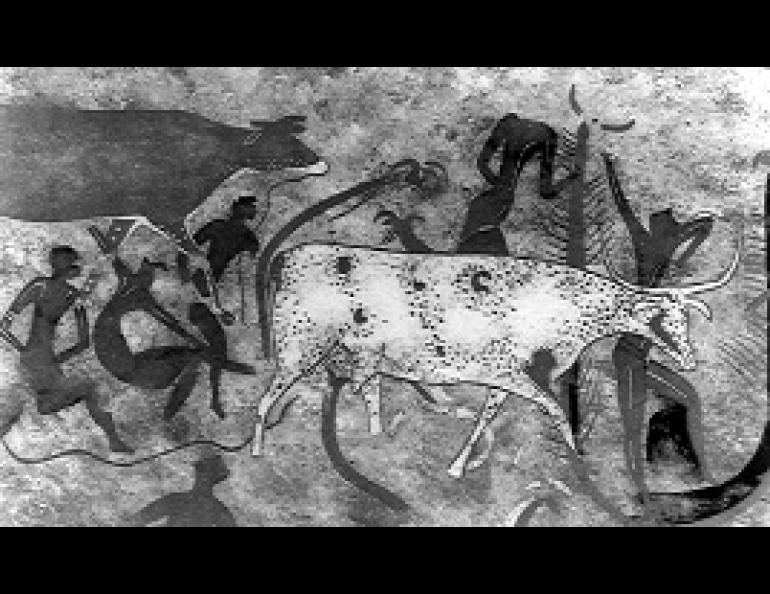

White spotting in domestic animals goes back for at least several thousand years. Cretan wall paintings show spotted bulls, Egyptian frescoes show piebald chariot horses and spotted oxen, and of course the bargain between Jacob and Laban in Genesis presupposes the existence of spotted goats. I suspect at least part of the reason that white spotting is so common in domesticated animals lies in the process of domestication. Domesticated animals are descended entirely from those wild animals that were unchoosy enough about their mates to reproduce in captivity. (Zookeepers trying to maintain endangered species are worried that they may unintentionally be domesticating them in the process due to this effect.)

If a spotted animal occurred in a domestic herd, it would normally mate and produce offspring carrying the spotting genes. Furthermore, the spotted animals would be relatively visible to herders and readily identifiable as domestic, and might have been unconsciously favored for these reasons. (This would be particularly true of early herding dogs, which probably looked very much like wolves. A herding dog with white markings would be far less likely to be killed by a shepherd thinking he was defending an early flock than would one that looked just like a wolf.)

If a particularly desirable trait, such as high milk production, happened to occur in a spotted animal, that animal would be heavily used for breeding, and spots would multiply along with the desirable trait. It is even possible, through a phenomenon called linkage, that the offspring carrying the parent's improved trait would be the spotted ones.

If Jacob's wage agreement with his father-in-law were at all typical, herdsmen who had observed that offspring frequently resembled the sire would have encouraged the spotted males to breed as many females as possible, possibly even removing solid males selectively. And, of course, spotted animals may have been favored for the same reason that full white ruffs are favored in Collies today -- just because their owners thought they looked pretty.

Related articles are available on black, brown and yellow in dogs , overdominant dilution genes , banded (agouti) hair in mammals , and Siamese coloration in cats .