Rock Glaciers

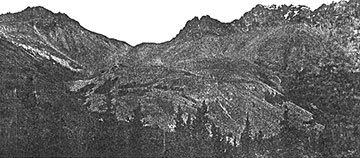

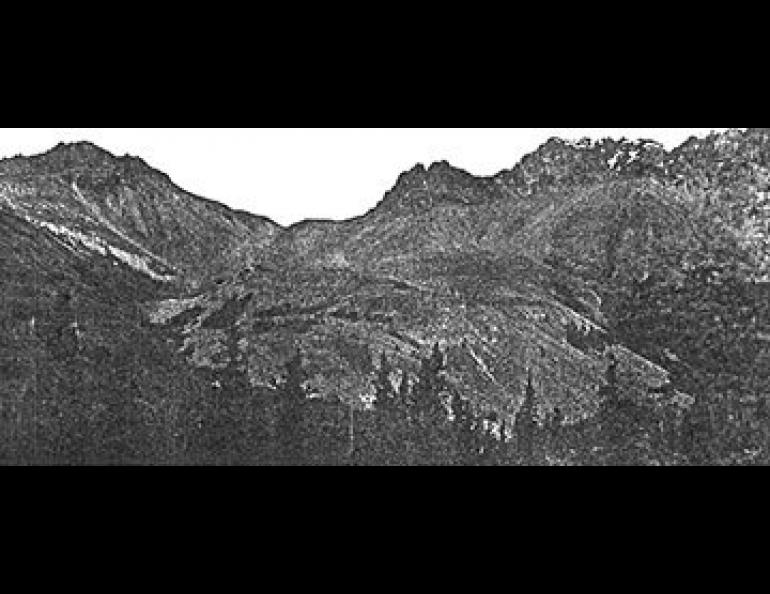

An active rock glacier is a stream of blocky rock containing ice in the interstitial spaces (the voids between the rocks) that flows downslope by virtue of viscous (molasses-like) flow within the ice component. The top of an active rock glacier flows faster than its base. Consequently, near the toe of a rock glacier, material from the top rolls or slides down the front of the rock glacier to form a slope lying at the angle of repose of the loose rock composing the glacier. By means of this characteristic slope at the toe, one can recognize the rock glacier and that it is active and moving.

Rock glaciers occur by the hundreds in the Alaska Range. They occur in the Wrangells and many other mountain ranges around the world including the San Juan Mountains of Colorado and the Sierra Nevada of California.

For a rock glacier to exist several conditions must be met. There must be a source of blocky rock such as a weathering cliff or mountain slope or perhaps even the terminal moraine of a dying ice glacier. Secondly, the mean annual temperature must be low enough for water percolating down through the blocky rock to freeze and form an ice matrix in the spaces between the rocks. In other words, the temperature must be low enough to support permafrost. Third, there must be a slope for the rock glacier to flow along since the force that gives it life is gravity.

The upper surfaces of active rock glaciers in the Alaska Range have been observed to move forward about a meter per year, whereas the motion of the front is about half that amount. The top surface often shows longitudinal ridges and, near the front, transverse ridges convex downslope appear.

If the source of rock debris disappears or if the climate warms up, an active rock glacier will become inactive. Consequently, the study of rock glaciers can yield information on past climatic changes.