The Second-to-last Great Alaska Earthquake

Rod Combellick sounded downhearted on the phone. It was the voice of a prophet with no honor in his own land.

"About that article on the prehistoric Seattle-area earthquakes," he said. "Do you know about our work on past earthquakes in southcentral Alaska? It's really very similar." Well, no, I didn't. To remedy that, Combellick sent a copy of a forthcoming paper.

The column on earthquakes near Seattle he referred to explained how researchers discovered a big quake had occurred right under the city's site a thousand years ago. The group responsible for the work in southcentral Alaska is the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys, for which Combellick is Chief of the Engineering Geology Section. And the paper reports how he and his colleagues think that a whopping great earthquake, one with a magnitude between 8 and 9, rends the region from the Copper River Delta past Cook Inlet an average of every 600 to 800 years.

Scientifically speaking, the Alaskans have an experimental edge on their colleagues to the south. In Washington state, no seismologists were around to study the last major earthquake under Seattle or its immediate aftermath in or about springtime 991. In Alaska, scientists were swarming over the countryside almost as soon as the shaking stopped on Good Friday of 1964.

Thus they've had a unique chance to observe the immediate and long-term changes brought about by a great earthquake. For example, they have quantified how much the ground surface changes in a seismic event of that high magnitude. During the 1964 earthquake, some portions of southcentral went down by more than six feet. Combellick says that a "downwarp of as much as 2 m[eters] occurred over an elongate region including Kodiak Island, Kenai Peninsula, most of Cook Inlet, and Copper River Basin. Uplift as much as 11.3 m occurred seaward of the subsidence zone," which means an awful lot of terrain changed altitude significantly in just a few minutes. Since 1964, some of the sunken areas have rebounded, and others have been buried in silt. Alaska scientists have observed what happens to a coastal forest when its floor subsides under salt water, and they've seen how long it takes for a southcentral marsh to be smothered and preserved under inorganic muds.

With clear evidence from this titanic experiment in the recent past, scientists have found similar clues from the more ancient past. Elevated terraces on Middleton Island, which lies far offshore of Prince William Sound, record five uplift events before the one in 1964. They were spread over the past 4900 calendar years. Buried peat and forest layers in the Copper River Delta record four pre-1964 uplifts during the past 3000 years; the last one appears to have occurred between 665 and 905 years ago.

The evidence upon which Combellick's paper concentrates is found in a buried forest near Girdwood, southeast of Anchorage along Turnagain Arm. There the remains of a forest killed by salt water after the ground sank in 1964 are underlain by the stumps of a forest killed far earlier. Radiocarbon dating of the ancient stumps and the peat in which they are rooted indicates they died probably between 744 and 946 years ago, consistent with the event at Copper River Delta. Similar ages have been found for buried marshes at four other sites along Turnagain and Knik Arms.

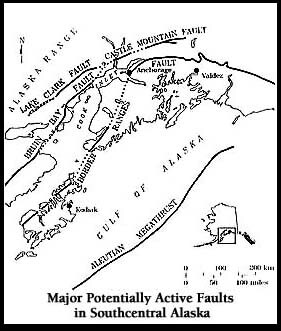

It's important to note---and Combellick makes the point emphatically---that even if there is an 800-year gap between monstrous earthquakes in the Anchorage area, it doesn't mean southcentral residents can forget about seismic hazards for the next several centuries. The regions crossed by many active faults perfectly capable of generating more powerful quakes than any that have shaken California since World War II, and those "little" temblors have collapsed freeways and buildings.