See you in Saskatchewan, said the swan

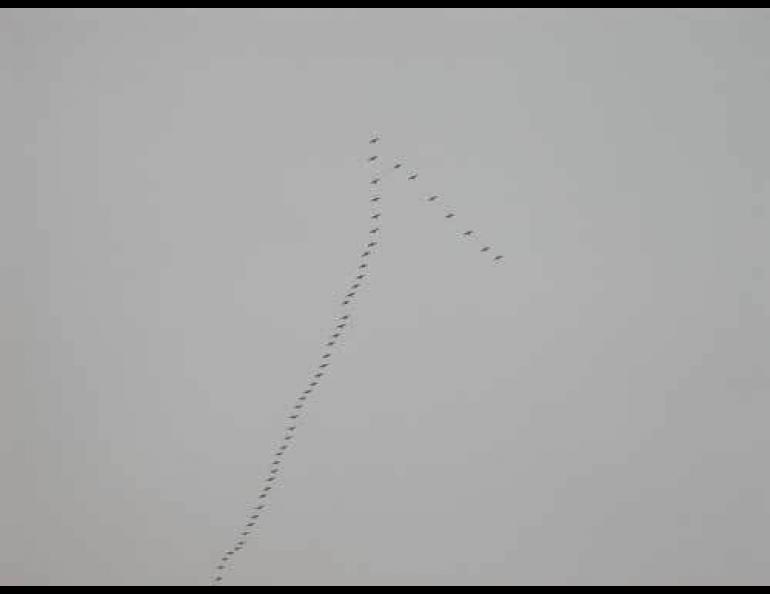

A couple of weeks ago, at a time I assumed most migrating birds were long gone, a flock of swans flew overhead in a formation that resembled a check-mark headed out of Alaska. As the birds silently wafted out of sight, I wondered where they might be headed.

Not long after that, a biologist emailed me to show the results of his summer work—the migration paths of about 50 tundra swans he and his coworkers had fitted with satellite transmitters. Looking at their progress now on Google Earth, I can see that a swan took off from the pothole lake country southeast of Selawik in early October, flew over my vantage point in Fairbanks on October 6th, took a hard right through North Pole and continued down a path roughly above the Alaska Highway. Around Calgary, the bird made a run east to a huge reservoir in Saskatchewan farm country. From there, the bird turned around and made its way to where it now stands, or maybe floats, in early November: a circle-pivot irrigated field near Dairy, Oregon.

Though the bird with the transmitter flew over one day before I noticed the group of swans, it’s a good bet it was coming from the same place. Craig Ely, a waterfowl biologist with the U.S.G.S. Alaska Science Center in Anchorage, said that tundra swans are gregarious enough that birds spending summer in the same place often follow similar flight paths when they migrate in and out. This fall and perhaps into fall 2009, Ely and his colleagues are following 48 tundra swans with precision he never dreamed of when he started studying swans 20 years ago.

During July and August of summer 2008, biologists went to five different regions where tundra swans hang for the summer and hatch brand-new cygnets—near Cold Bay, King Salmon, the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta, Kotzebue Sound, and the mouth of the Colville River on Alaska’s North Slope. With dip nets and other tools, the biologists captured the temporarily flightless birds (because they were molting—replacing some flight feathers) and surgically implanted satellite transmitters in the abdomens of 10 birds at each location. The transmitters are less obtrusive to the birds than those wrapped around the neck or worn as a backpack, Ely said, and they should be good for two years, which will at least allow biologists to track next spring’s migration back to Alaska.

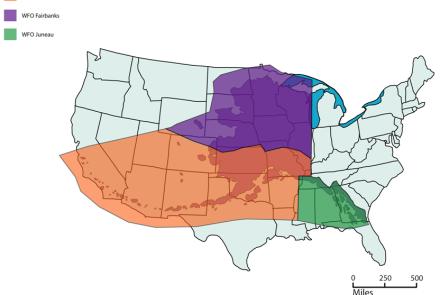

As for the fall migration, Ely learned that tundra swans around Cold Bay don’t migrate out of Alaska, as some biologists thought; that some King Salmon birds migrating to California go all the way inland to Saskatchewan during the trip; and that Colville River swans, known to spend winters on the East Coast of the U.S., also visit Saskatchewan before taking a hard left through North Dakota and heading east.

“There must be good habitat in Saskatchewan, or else why would birds going to (both the east and west coasts) make a big, looping migration to go there on the way?” Ely said.

By following the birds he tagged this summer, Ely has learned many things he didn’t know, especially the swans’ use of remote habitats at northern staging areas before migration and some details about swan migration biologists had only guessed at before.

“This validates a lot of the data that’s already in textbooks,” he said.

Tracking the birds on the Internet is also a bit of fun for people who want to follow the last birds to leave Alaska and the first to arrive back next spring, which seems like a long time from now. (alaska.usgs.gov/science/biology/avian_influenza/TUSW/index.html)