Tamarack -- Not A Dead Spruce

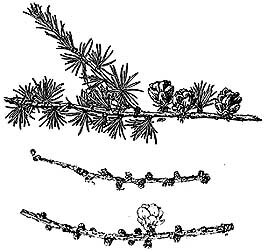

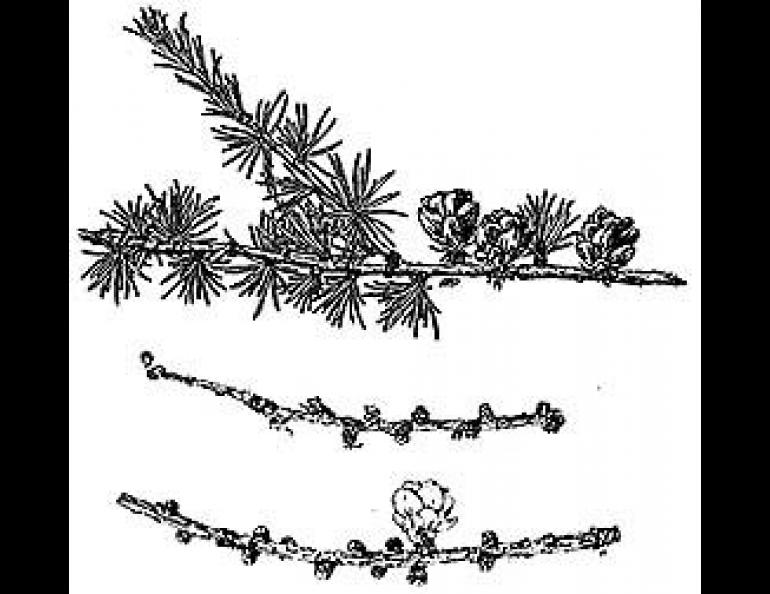

The Cooperative Extension and U.S. Forest Service offices in Fairbanks often receive queries in the fall from distressed landowners who want to know what they can do to save their spruce trees. Usually the solution is to leave the trees alone, for they are healthy tamarack and not dying spruce. Tamarack, or eastern larch, is Alaska's only deciduous conifer and people unfamiliar with it are often fooled by the falling needles as winter approaches. Tamarack have very distinct "bumps" (short shoots) on their twigs and branches, and their cones usually sit upright on the branches, whereas those of the spruce--alive or dead--hang down.

Tamarack commonly grows on cold, wet sites and its growth rate and appearance do little to stimulate interest. When one of these trees finds itself on a better site, however, it shows a remarkable change of pace. Individual tamarack growing in white spruce stands may achieve a size comparable to white spruce 100 to 150 years old. The current record tamarack in Alaska stands near mile 311 of the Richardson Highway. It is 13 inches in diameter 46 feet from the ground (referred to as diameter at breast height or dbh) and is 77 feet tall. That's a fair size for a tree in interior Alaska, but the record tamarack for the U.S., located in Maine, is 36 inches in diameter and 95 feet tall. One can see a number of examples of excellent tamarack trees growing as ornamentals around Fairbanks.

Dr. Ed Packee, a forester with the University's Agriculture and Forestry Experiment Station, is urging a close look at tamarack as a tree for the future in interior Alaska. He has several reasons for believing that tamarack could one day play a more important role in the state's managed forests. First, its growth during the juvenile period (20-30 years) is rapid, similar to that of aspen and birch which grow much more rapidly than white spruce during the juvenile stage. Second, tamarack seems to grow better than the other Interior species on relatively cold, wet sites--a common condition in Alaska. Third, tamarack produces a denser wood than the other conifers, more like that of birch. This means that it might be possible to produce more wood fiber on a given site planted with tamarack than with the other conifers. Fourth, the heating value of a cord of tamarack is about the same as that for a cord of birch, much better than other conifers. Finally, tamarack wood has properties that make it resistant to decay. Thus, the untreated wood bears up well when placed in contact with the ground, as, for example, when used as fence posts or sill logs for a cabin.

When confronted with the question of why tamarack does not occur more widely in the Interior, Dr. Packee suggests the following reasons: The species is a favorite food source of hares and they may limit its survival. There are several species of insects in Alaska that weaken or kill tamarack; one, the eastern larch beetle, killed more than one-half the commercial-size tamaracks in Nova Scotia between 1978 and 1983. In addition, tamarack tends to require open conditions--that is, a lot of sun- in order to grow best, and it may not be able to become established after other trees are growing in an area.

It is not possible to foretell if tamarack may some day become a commercial crop, but one thing is certain: the "spruce that dies" each fall has some unique qualities that make it a desirable tree for ornamental, subsistence and commercial uses in interior Alaska.