Twenty years of the Alaska Volcano Observatory

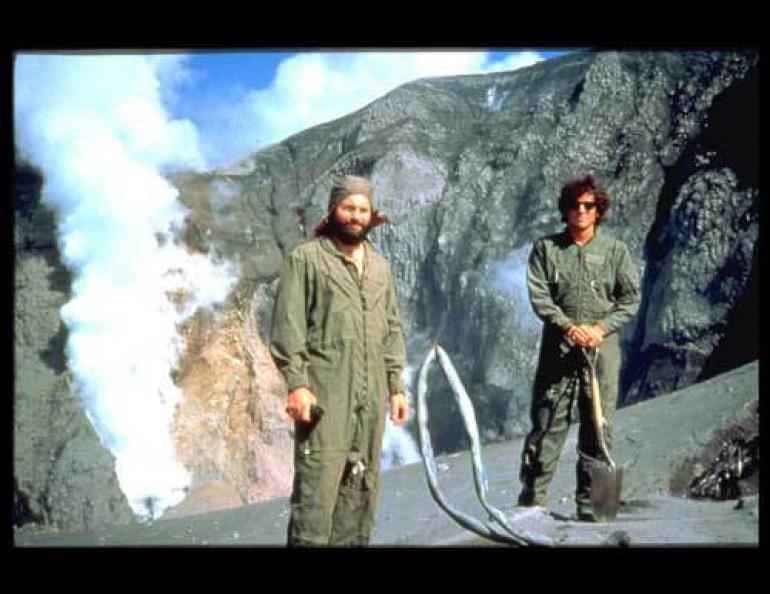

Twenty summers ago, earthquakes rocked the town of King Cove on the Alaska Peninsula. Some people were so worried that the nearby volcano, Mt. Dutton, was going to erupt that they caught flights out of town. Others called in the cavalry—members of the fledgling Alaska Volcano Observatory.

In 1988, John Power had just finished his master’s degree when he became the observatory’s first full-time employee. He flew out to King Cove with a few colleagues to check on the volcano.

“I remember that the biggest earthquake happened in August, on 8/8/88,” said Power, a geophysicist with the USGS Alaska Science Center who still works for AVO in Anchorage. “It happened right at the peak of salmon season, so there were a lot of people in town.”

After installing a few seismometers on the flanks of 4,800-foot Mt. Dutton, eight miles from King Cove, Power and his comrades saw that the character and the size of the earthquakes didn’t suggest that Mt. Dutton was going to explosively erupt that August.

“We told people, ‘we’ll watch it, but evacuation doesn’t make sense right now,’” Power said.

While spending a few weeks in King Cove and bunking at the Peter Pan cannery, Power noticed the earthquake activity waning, showing that the volcanologists had made the right call. The brand-new Alaska Volcano Observatory was one-for-one in advising people what to do, or, in the case of Mt. Dutton, what not to do.

Since that first response in 1988, the Alaska Volcano Observatory has grown from a good idea lobbied for by scientists—including John Davies, Syun-Ichi Akasofu, John Filson, and Tom Miller—into a team of people in Anchorage and Fairbanks who have their fingers on the pulse of more than 30 volcanoes in Alaska. The observatory is a cooperative program of the Geophysical Institute, the USGS and the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys. The job of the experts there is to monitor volcanoes and give Alaskans information when they need it most.

“Alaska has more explosive eruptions than any other state,” said Jon Dehn, an associate research professor at the Geophysical Institute, “It’s AVO’s responsibility to be prepared so the average person doesn’t have to worry about it.”

Like other AVO scientists tuned into Alaska’s volcanoes, Dehn is never far from his cellphone, which rings with Jimmy Buffett’s “Volcano” when an Alaska volcano shows signs of unrest. He and other AVO scientists now monitor an impressive data stream, which was just a trickle in 1988.

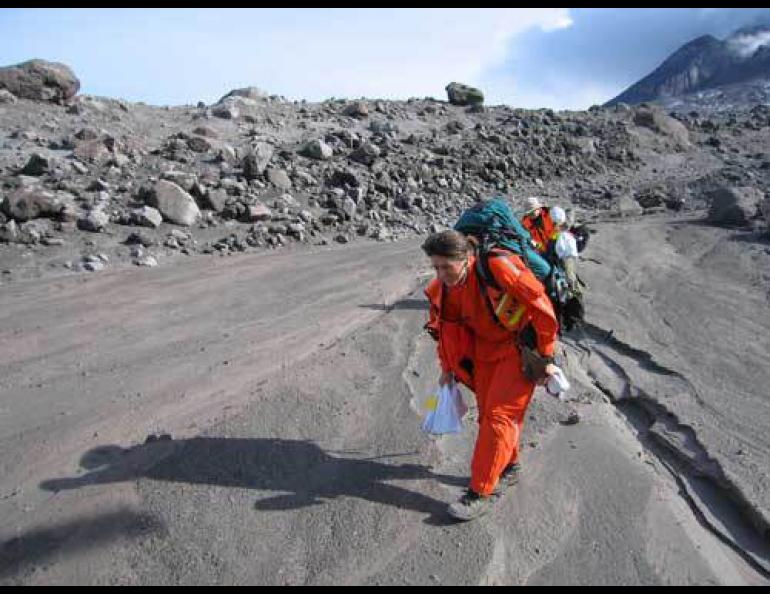

The last two decades have seen the development of satellite sensors that allow people to check for volcano hotspots several times a day, precise GPS receivers that enable scientists to watch volcanoes inflate and deflate, infrasound sensors that record sudden changes in air pressure during explosive eruptions, and the advent of a helpful tool called the Internet.

“When AVO was founded, there was no e-mail,” Power said.

“We were really kind of winging it in 1988,” Dehn said. “But in ’08, our game is pretty tight.”

Nowhere was that more evident than during the 2006 eruption of Augustine Volcano, across Cook Inlet from Homer. AVO not only predicted the eruption, but also forecast the migration of ash clouds (which can shut down aircraft engines).

“We ended up with the best dataset we’ve had so far,” said Steve McNutt, coordinating scientist at AVO and a research professor at UAF’s Geophysical Institute.

Other improvements to the volcano observatory include the late 1990s instrumentation of volcanoes in the Aleutians. Right now, scientists are monitoring most of the potentially dangerous volcanoes that make up the remote islands, which about 80,000 large jets fly over each year. That wasn’t the case when McNutt joined AVO in the early ‘90s, when a volcano named Westdahl was spewing ash into the sky.

"The first report was from a pilot who said Shishaldin (a nearby volcano) was erupting," said McNutt. "That’s what happened 16 or 17 years ago. Nowadays, we catch it first. We’re the ones telling airline pilots, not the other way around."