What big teeth this dinosaur had

A long time ago, a dinosaur named Troodon lived in the area where Alaska’s North Slope is today. Troodon was a meat eater that looked like an eight-foot bird, with the mouth and tail of an alligator. It stood on its hind legs and had short, muscular forearms that helped it clamp down on plant-eating dinosaurs, opossum-like creatures, and maybe fish. Compared to other dinosaurs, Troodon had very big eyes.

Troodon also had very big teeth. In fact, the Alaska version of Troodon had such large teeth that a scientist thinks it may have been the largest Troodon on the continent, and the dominant predator of the far north even though it wasn’t the biggest meat-eater.

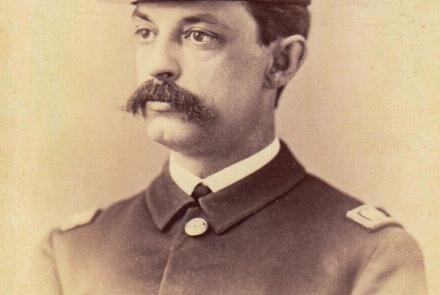

Tony Fiorillo has pondered the sharp, serrated teeth that he and other paleontologists have found on a dinosaur bone pit off the Colville River. Fiorillo, of the Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas, has compared them to teeth from Troodons recovered in Montana and southern Alberta, and he has found that Alaska Troodon’s teeth were 50 percent larger than its Lower 48 relatives. Because tooth size relates to body size, Fiorillo thinks Alaska Troodon may have been twice the size of lower-latitude versions.

Why would a far north dinosaur be larger than its cousins further south? The question is even more intriguing when one considers that Troodon’s home on Alaska’s North Slope 70 million years ago was probably located even higher on the globe than it is today. That means it was even darker in winter than at present, when Barrow residents don’t see the ball of the sun for more than a month. Though the swings of daylight were perhaps larger back then, the climate was much warmer. Today, the average temperatures along the North Slope are well below freezing, but Alaska Troodon probably experienced temperatures closer to what people feel today in the region stretching from northern Oregon to southern Alberta, Fiorillo said.

Troodon might have done well in the far north because of its large eyes that gave it an advantage in lower-light conditions. Seeing better may have led to longer hunting hours, or more successful hunting as compared to the Gorgosaurus, a relative of Tyrannosaurus rex that was larger than Troodon, and possibly present on the North Slope too.

“Troodon was the top-tier predator,” Fiorillo said. “I would still expect that plant-eaters (were more numerous) up there, but (Troodon) was the most dominant meat-eating dinosaur up there.”

Fiorillo, who has been traveling to Alaska to study dinosaurs for more than a decade, calls the state “a great big candy store.” He and his colleagues recently found “thousands and thousands” of meat-eating dinosaur footprints in Denali National Park that help fill in the picture of prehistoric Alaska.

“The North Slope bones tell us who was at the party, and Denali tells us what the dance was,” Fiorillo he said.

Fiorillo will travel back to Denali Park this summer, and he also plans a journey into Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. It seems the more scientists look in Alaska, the more they find, and they have already discovered enough to imagine what Alaska was like in the time of the dinosaurs.

“What’s really great about the North Slope, Denali, and Aniakchak National Monument is that just those three areas give us enough to do a detailed ecological reconstruction of Alaska 70 million years ago,” he said. “What better baseline (for climate change) information could you get than looking at Alaska 70 million years ago when it was in a greenhouse mode?”