Why Lower 48 Fruit Trees Don't Do Well in Alaska

Newcomers to Alaska will frequently order young pine, fruit or maple trees from their home state in the lower 48. They enthusiastically proclaim that the trees should do well here because the temperatures in Montana, or Minnesota, or North Dakota, or wherever they're from frequently plummet as low as they do in Alaska. The trees do just fine back there, they say. But too often, they find that after a winter or two, their trees have died in Alaska.

Professor L.J. Klebesadel, writing in Agroborealis, a publication of the University of Alaska's Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, tells why the efforts of the would-be transplanters often fail.

There's more to it than just how cold the temperatures get. The main factor is what Klebesadel calls "photoperiod." Simply stated, that's the amount of sunlight--and the intervals at which the sunlight is received--over the course of a year.

Perennials from more southern sources fail to survive winters in Alaska not because the winters are colder (sometimes they're not), but because conditions here during late summer and autumn are different from their place of origin. Although they may possess the genetic potential to adapt, when they are abruptly transported far north of their origins, they experience too brief a span of short photoperiods prior to killing frost (that is, the days get too short too fast). Hence, plants introduced from more southerly latitudes have not been previously induced to prepare rapidly for Alaskan winters.

When North America was settled by Europeans, many of the farmers traveling to the New World brought their conventional crops with them, and they did just fine. In fact, most of the perennial agricultural crops grown today in the northern half of the lower 48 are species introduced from Europe, where the latitude is similar to that of the northern contiguous states.

When the farmers began their northward migration to Alaska, many tried to grow those same varieties on their northern farms, often without success. Even though the imported strains could be successfully cultivated for thousands of miles in an east-west direction, when transported northward, they were unable to adapt.

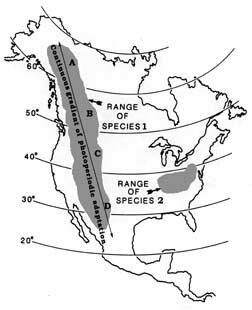

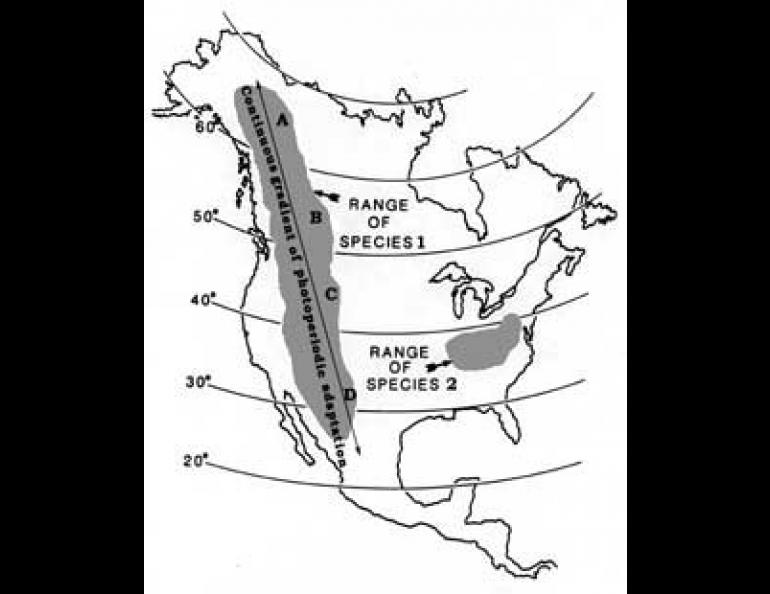

This is not too surprising, except when one stops to consider that there are species of trees and plants that flourish from the Mexican border to Alaska. The big difference is that they represent different "ecotypes," or variations within the same species, which have managed to adapt to widely varying environments. In other words, there are some species that are able to adapt to widely varying sunlight hours (or temperatures, or moisture conditions), and there are some that cannot.

The basic difference underlaying why some plants will grow here while other species will not, as Klebesadel states, is as follows: as plants migrated on their own during ancient times, they moved only very short distances each year. Under such conditions, plants at the leading edge of plant migration did not abruptly enter totally new climatic regimes. In contrast, when an Alaskan grower orders seeds from outside, the plants grown in Alaska are subjected immediately to an unaccustomed pattern of seasonal climatic effects. This pattern of environmental influences, especially during late summer and autumn, is critically different from that which their ancestors were accustomed to in preparing for winter in their area of origin.