The World's Deepest Hole

On Russia's Kola Peninsula, near the Norwegian border at about the same latitude as Prudhoe Bay, the Soviets have been drilling a well since 1970. It is now over 40,000 feet deep, making it the deepest hole on earth (the previous record holder was the Bertha Rogers well in Oklahoma--a gas well stopped at 32,000 feet when it struck molten sulfur).

It is not oil or gas that is being sought with the Kola well, but an understanding of the nature of the earth's crust. The United States began a similar investigation, called Project Mohole, in 1961. This project, which was intended to penetrate the shallow crust under the Pacific Ocean off Mexico, was abandoned in 1966 because of lack of funding.

It's possible to draw a reasonable cross section of the earth based purely on remote geophysical (largely seismic) methods, but unless on-the-spot checks can be made, there will always be a certain amount of guesswork involved. Digging down to take a look compares with studies made from the surface in the way that exploratory surgery compares with taking an X-ray.

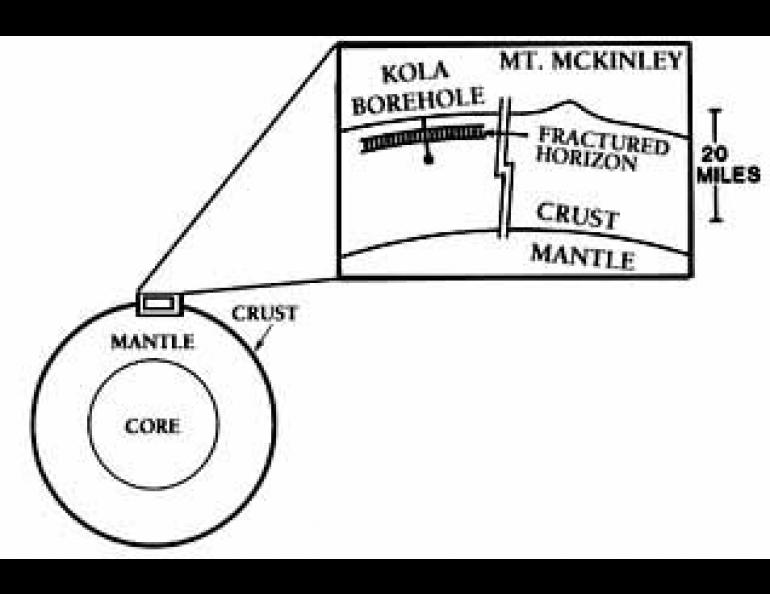

There is now no reasonable doubt that over the continental areas of the world the earth's crust is about 20 miles thick, but only about half that in the oceanic areas. In both cases, the crust overlies a mantle which can be detected because it transmits seismic waves at a distinctly higher velocity than does the crust, although there are also velocity variations within the crust itself.

In 1926, British geophysicist Harold Jeffreys proposed that this transition zone within the crust, identifiable on seismic records around most of the world as a "jump" in seismic velocity, could be attributed to a change in rock type from granite to a denser "basement" of basalt (basalts can be seen at the surface when they emerge as lava flows). For years, this concept has served well as a working hypothesis for earth scientists.

The Kola well has now penetrated about halfway through the crust of the Baltic continental shield, exposing rocks 2.7 billion years old at the bottom (for comparison, the Vishnu schist at the bottom of the Grand Canyon dates to about 2 billion years--the earth itself is about 4.6 billion years old). To scientists, one of the more fascinating findings to emerge from this well is that the change in seismic velocities was not found at a boundary marking Jeffreys' hypothetical transition from granite to basalt; it was at the bottom of a layer of metamorphic rock (rock which has been intensively reworked by heat and pressure) that extended from about 3 to about 6 miles beneath the surface. This rock had been thoroughly fractured and was saturated with water, and free water should not be found at these depths!

This could only mean that water which had originally been a part of the chemical composition of the rock minerals themselves (as contrasted with ground water) had been forced out of the crystals and prevented from rising by an overlying cap of impermeable rock. This has never been observed anywhere else.

In addition to the important bearing that this discovery has on the general geophysical sciences, there is a potential economic impact. This water (variously known as "water of crystallization", "primary" water, or "juvenile" water) which originates as an integral part of the rock crystals is very highly mineralized, and is a primary concentrating agent for most ore deposits.

The technology for mining the depths at which the solutions occur, however, is not yet available. In order to get their single drill hole down as far as they did, the Soviets had to resort to experimental methods. Their chief innovation was that, instead of turning the drill bit by rotating the stem, in the Kola well the bit alone was turned by the flow of drilling mud. In this manner, they were able to eliminate rotation of the entire drill string above.