Alaska-developed volcano monitoring system will expand across U.S.

A new radar-based volcano monitoring system developed by the University of Alaska Fairbanks and U.S. Geological Survey will expand across the U.S. and beyond.

The expansion, funded by NASA, could lead to earlier detection of volcanic unrest.

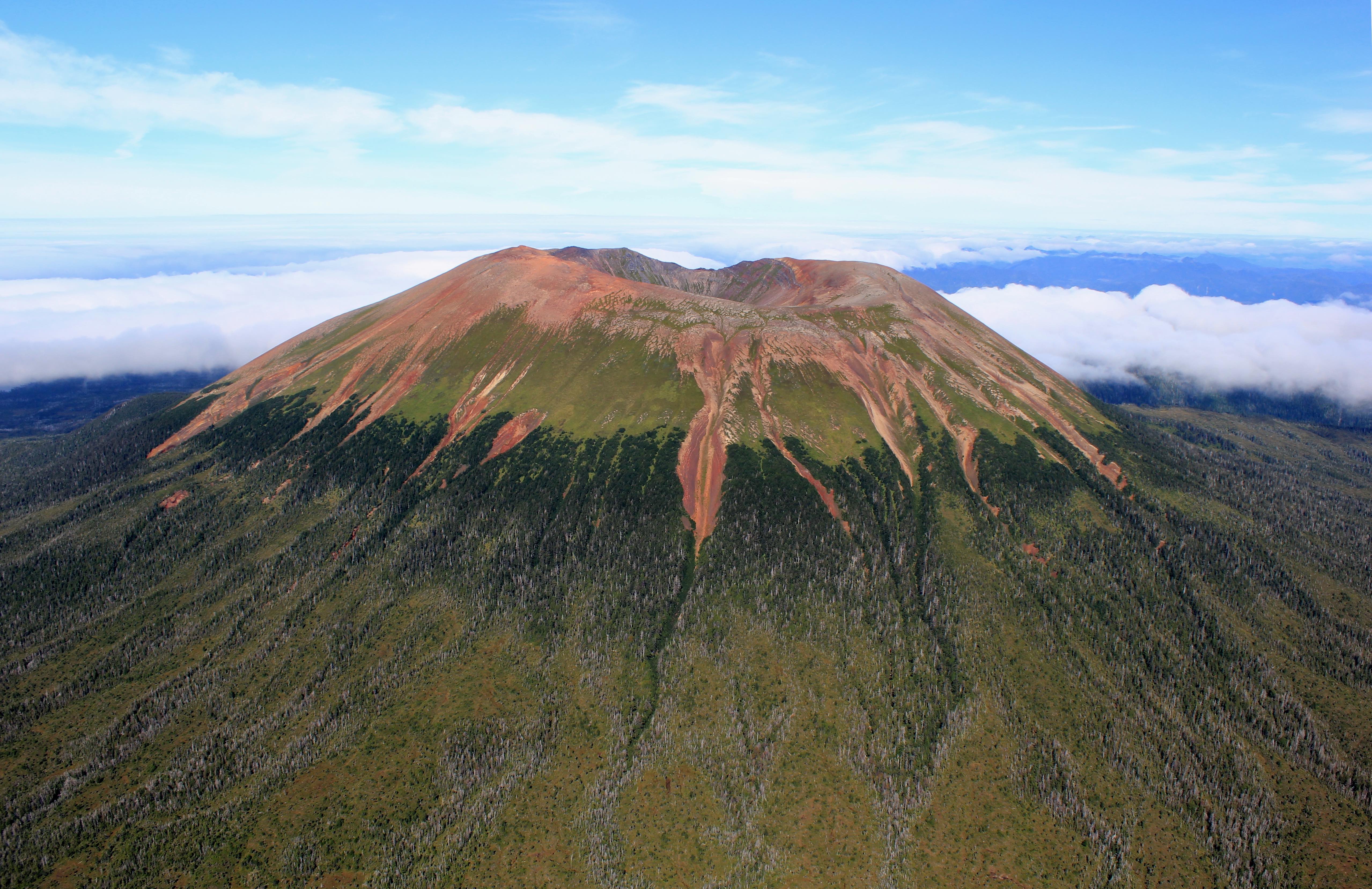

The Alaska Volcano Observatory at UAF has been using a prototype of this system, named VolcSARvatory, since early 2022. Its usefulness was immediately apparent when a swarm of earthquakes occurred at long-quiet Mount Edgecumbe volcano, near Sitka, Alaska, on April 11, 2022.

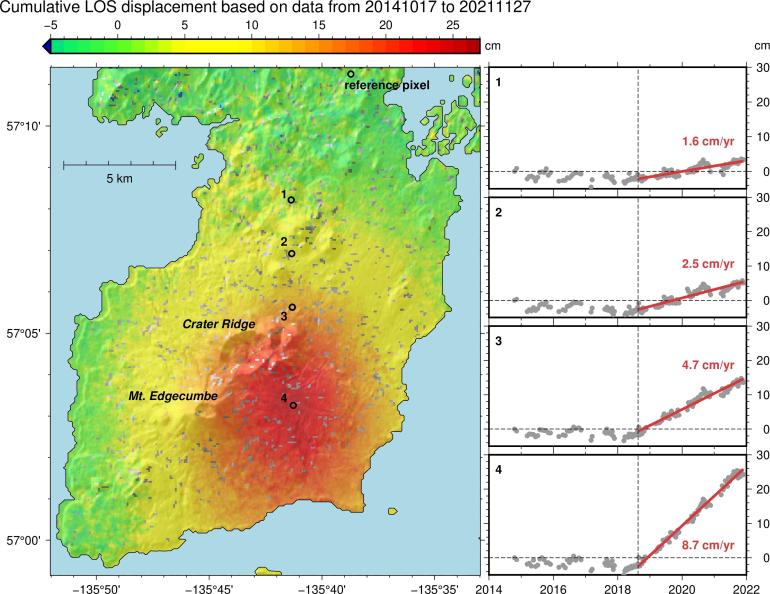

VolcSARvatory uses interferometric synthetic aperture radar, or InSAR, to detect ground movement changes as small as 1 centimeter. It works by combining two or more satellite radar images of the same area taken at different times. Long-duration surface changes can be chronicled by collecting repeated images to build a time series of data from a single location.

Franz Meyer, a remote sensing professor with the Geophysical Institute and the UAF College of Natural Science and Mathematics, said expanding the system to all USGS volcano observatories in collaboration with USGS Volcano Science Center colleagues will provide a consistent approach to monitoring active volcanoes.

Meyer is also chief scientist for the institute’s Alaska Satellite Facility, which co-developed the VolcSARvatory prototype system with the Alaska Volcano Observatory and researchers in the Geophysical Institute’s remote sensing group.

“Technology has evolved to a point that we can now make the system operational at a national scale,” Meyer said.

The VolcSARvatory system streamlines satellite radar analysis in a cloud computing environment, which allows the processing and analysis of vast volumes of data in only a handful of days. The process would otherwise require several weeks.

The system proved valuable in studying Mount Edgecumbe’s unexpected activity.

In 2022, a team from the Alaska Volcano Observatory and Alaska Satellite Facility began analyzing the previous 7 1/2 years of Mount Edgecumbe data using the VolcSARvatory prototype and found deformation began 3 1/2 years earlier, in August 2018. Subsequent computer modeling indicated an intrusion of new magma caused the ground deformation.

“We weren't aware of what Mount Edgecumbe was doing because there was no ground instrumentation,” said geodesy professor Ronni Grapenthin with the UAF Geophysical Institute and the Alaska Volcano Observatory. “The InSAR analysis that we did with the early version of the system highlighted that there had been years of activity that we just didn't know about.”

The USGS Volcano Science Center, which helped develop VolcSARvatory, operates the Alaska Volcano Observatory and four other U.S. volcano observatories. AVO is a joint program of the UAF Geophysical Institute, the USGS and the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys.

Michael Poland, a geophysicist with the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory and scientist-in-charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, is a collaborator on the VolcSARvatory project and has been a proponent of using InSAR for volcano monitoring and research.

“We have long used InSAR to track deformation at volcanoes in the USA,” Poland said, “but the work has been done in a piecemeal fashion to this point. VolcSARvatory will provide situational awareness of volcano behavior and possibly identify volcanoes that are becoming restless before other indications, like earthquake activity, show up.”

Using InSAR-type satellite data will enhance the monitoring of volcanoes that have been fitted with ground sensors and will allow for the monitoring of the many others that don’t have ground-based stations.

“We’re using a lot of other observations that are satellite-based, such as gas, thermal and visual remote sensing to monitor those volcanoes, and surface deformation adds an important indicator of volcanic activity,” said Grapenthin, who serves as project liaison to AVO and the Volcano Science Center.

Surface deformation can reveal the location and volume of new magma and gases. It can also indicate whether pressure is building due to that new magma or gas, or whether the system is depressurizing as magma and gas either move to other underground locations or approach an eruption at the surface.

The new system won’t operate by itself.

“There’s definitely a need for human quality control and interpretation,” Grapenthin said.

The UAF project is one of seven NASA selected from 60 submitted as part of the space agency’s Disasters Program. The seven winning proposals, announced Dec. 20, will share $6.3 million over two years.

• Ronni Grapenthin, 907-474-7286, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, rgrapenthin@alaska.edu

• Franz Meyer, 907-474-7767, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, fjmeyer@alaska.edu

• Rod Boyce, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-7185, rcboyce@alaska.edu