Fossil tracks push range of large bird northward

Scientists from Fairbanks, New Mexico and Japan have discovered the first reported fossilized tracks of a large four-toed bird that inhabited central Alaska 90 million to 120 million years ago.

A description of the two tracks was published in August in a special edition of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin and presented Wednesday at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Minneapolis.

The bird tracks were found in 2023 in mid-Cretaceous rock near the communities of Nulato and Kaltag. The location significantly extends northward the known geographic range of this type of track.

The work was led by paleontologist Anthony Fiorillo, executive director of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.

The August paper’s co-authors include University of Alaska Fairbanks geology professor Paul McCarthy with the UAF College of Natural Science and Mathematics and UAF Geophysical Institute, and associate professor of paleontology Yoshitsugu Kobayashi of Hokkaido University.

“Rather than a geographic oddity, we submit that the tracks described here offer further insight into the importance of the ancient Arctic in terms of bird biodiversity,” the authors write.

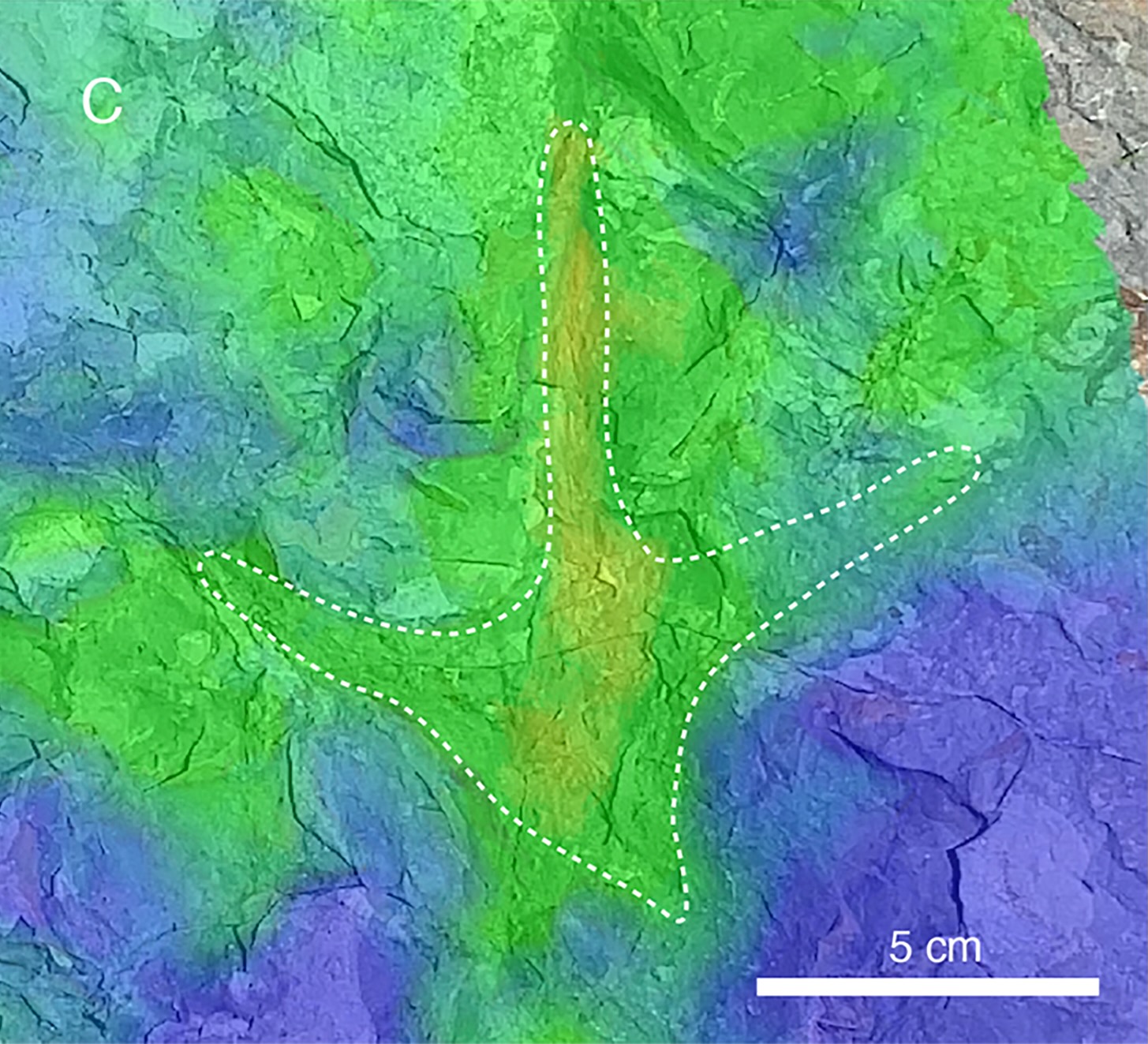

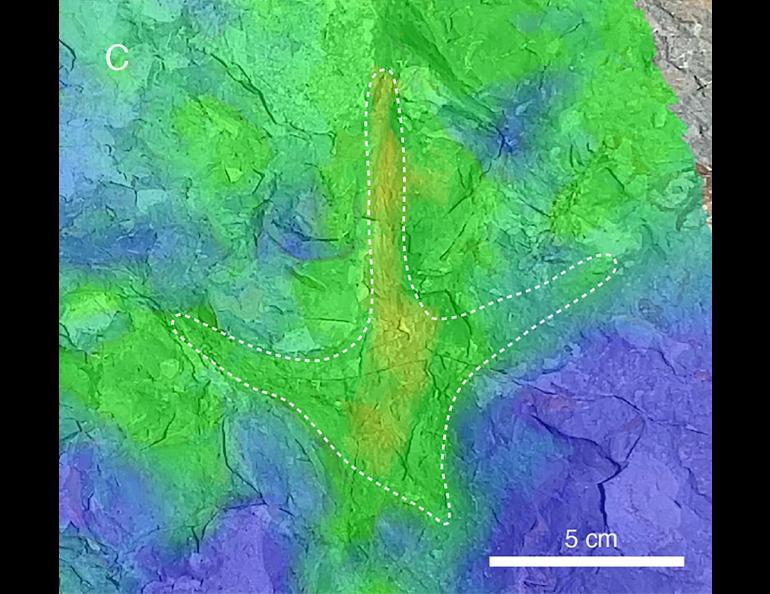

The newly discovered fossil tracks, found among several fossil tracks of smaller birds, are of a large four-toed bird and show three toes pointing forward and one pointing toward the rear. The toes are unwebbed.

“We found a fair number of fossil bird footprints,” Fiorillo said. “We found smaller bird footprints that would belong to something comparable to a modern-day shorebird such as a willet or an avocet.

“Then we found the footprints that are much larger,” he said. “They were more crane size or slightly bigger, more like whooping crane size.”

Fiorillo places the tracks in the Archaeornithipus ichnogenus, a classification of the most primitive birds. Archaeornithipus was first coined in 1996 to describe fossil tracks found in Soria, Spain.

An ichnogenus is a classification used to group trace fossils such as footprints, burrows or feeding marks that share similar characteristics. Trace fossils represent the behavior of organisms but do not necessarily indicate the species that made them.

Fossil tracks of other comparably sized birds of that era have been found in Denali National Park and in the Chignik Formation in Aniakchak National Monument in Southwest Alaska. Those tracks, however, are all of large three-toed birds whose toes pointed forward.

“That might seem trivial — three toes versus four toes,” Fiorillo said. “But what that reverse toe does with modern birds is it allows them to perch instead of being on the ground all the time when they are not flying.

“So we’re now looking at two very large types of birds doing two very different things,” he said.

The finding of the Alaska tracks adds to understanding of the complexity of the biodiversity at the time, Fiorillo said.

The three researchers in August 2023 investigated mid-Cretaceous sedimentary rock outcroppings along the Yukon River in west-central Alaska to better understand the dinosaurs that were present and their environments close to the time of the formation of the Bering land bridge. The work is part of a larger undertaking to understand that era.

The researchers found the Archaeornithipus tracks in what had been a floodplain adjacent to a river during the mid-Cretaceous, McCarthy said.

The finds occurred next to an exposed channel under a bluff along the Yukon. The area contained numerous trace fossils of smaller birds and other dinosaurs, all previously known to have inhabited the region.

“It was where you would have had a lot of fine-grained material that was probably firm mud that would have taken a bird footprint in it without turning into soup,” McCarthy said.

That material was then buried and hardened over time. Those rocks, over millions of years, were eventually thrust to the surface.

McCarthy said there’s much more to explore. There hasn’t been major geologic fieldwork in the area for more than 40 years, he said.

“It’s still a frontier basin,” he said. “It’s been mapped, and we have a general idea of what’s out there, especially right along the river, but there’s a whole lot of detail about ancient sedimentation and environments that nobody knows because nobody’s been looking.”

• Paul McCarthy, University of Alaska Fairbanks, pjmccarthy@alaska.edu

• Anthony Fiorillo, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, anthony.fiorillo@dca.nm.gov

• Rod Boyce, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-7185, rcboyce@alaska.edu