Geophysics professor wraps up voyage exploring Amerasia Basin’s origin

A science cruise led by a University of Alaska Fairbanks researcher to investigate the origin of the Arctic Ocean’s Amerasia Basin has come to an end, with the research vessel Sikuliaq back at Nome after more than seven weeks at sea.

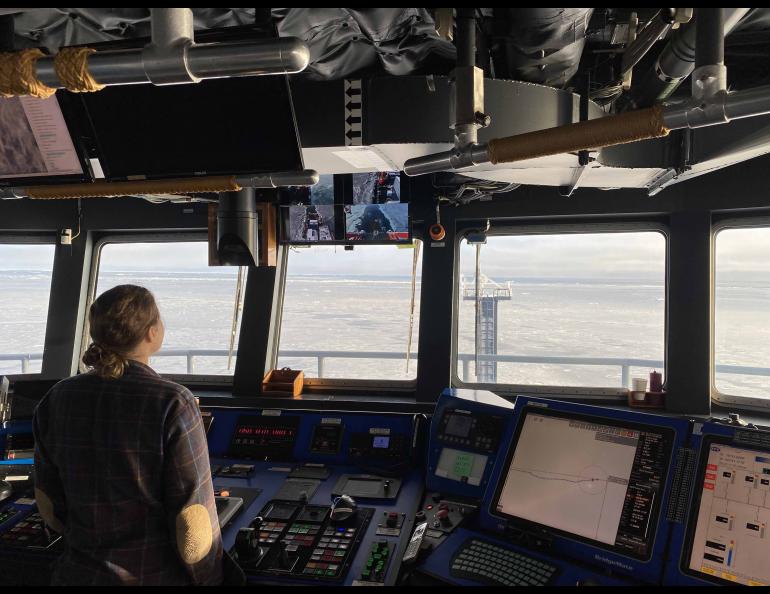

The voyage was the Sikuliaq’s northernmost to date. It sailed to just over 79 degrees 39 minutes north latitude in the Arctic Ocean, or about 500 miles north of Utqiaġvik on Alaska’s coast.

UAF Geophysical Institute geophysics professor Bernard Coakley, the project’s lead investigator, said in one of his final daily email updates that the cruise had some challenges.

“We have had to struggle against the ice. I think we managed, despite this struggle, to make good use of the ship's time and collect some uniquely valuable data,” he wrote on Sunday, Sept. 26. “We have only looked at very preliminary plots of the seismic reflection, ocean-bottom seismometer and sonobuoy data we collected underway, but the data appear to be very good, clearly imaging the underlying sediments and structures.

“During the next year(s), we will process these data to enhance the deeper features of the sedimentary section and learn about the history of the Borderland and Canada Basin,” he wrote. “I am looking forward to it.”

Coakley, the rest of the science party and the crew departed Seward on Aug. 10 with the aim of explaining the formation of the Amerasia Basin, one of the two large basins of the Arctic Ocean.

The National Science Foundation, which funded the research, owns the Sikuliaq. The vessel, a part of the U.S. academic research fleet, is operated by the UAF College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences.

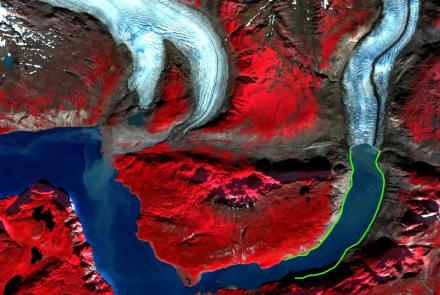

The plan called for the mapping of the northern edge of the basin’s Chukchi Borderland as well as the adjacent Canada Basin, a component of the Amerasia Basin that lies north of Alaska and Canada.

They collected multichannel seismic reflection data to gain information about the stratification and structure of the crust to reveal the basin’s history. They also gathered seismic refraction data by using ocean-bottom seismometers and sonobuoys, typically used to hunt submarines.

Coakley, in his Monday, Sept. 27, update, said he was surprised about the extent of the ice.

“The ice was not much by historical standards, but it was surprising in comparison to recent steady decay of the ice pack, both in thickness and extent,” he wrote. “The ice edge this year is well south of the recent years, though a large gap is seen in the central Canada Basin. While it seems we can anticipate continued retreat of the ice pack, we may not be able to predict where it retreats in a given year.”

In his final daily report, sent last Wednesday evening, Coakley described life on the remote research vessel.

“I like to say every cruise is a psychology experiment. We don’t plan this aspect of the science, but it happens every time when you bring a bunch of people together to do some tasks in isolation in occasionally stressful circumstances,” he wrote.

“Of course there is friction and frustration, but in the end we have managed to succeed both scientifically and socially.”

He also included in that final report, as he did with each daily update, a report on observed animals. The count in Wednesday’s update: seven walrus swimming together and 15 gray whales in a pod. Tuesday they saw one walrus, two bearded seals and an unidentified seal.

Bernard Coakley, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, bjcoakley@alaska.edu.

Alice Bailey, UAF College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences public information officer and Sikuliaq science liaison, 907-328-8383, alice.bailey@alaska.edu

Rod Boyce, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-7185, rcboyce@alaska.edu