When thousands of computer-controlled eyes begin looking out from an instrument aboard the James Webb Space Telescope in the coming months and years, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute associate research professor Gunther Kletetschka will be satisfied.

That’s because Kletetschka, prior to joining the Geophysical Institute in 2016, worked on shutter development for several years while at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, first as a postdoctoral researcher and then as a contractor.

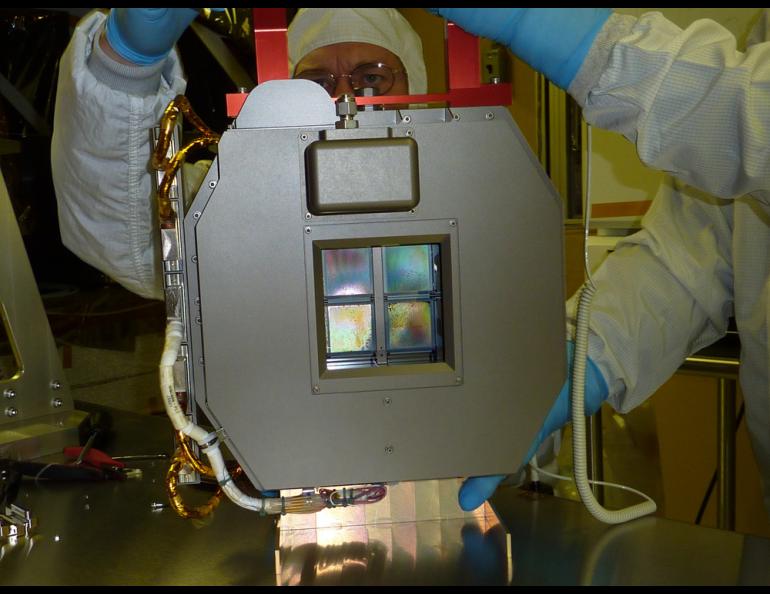

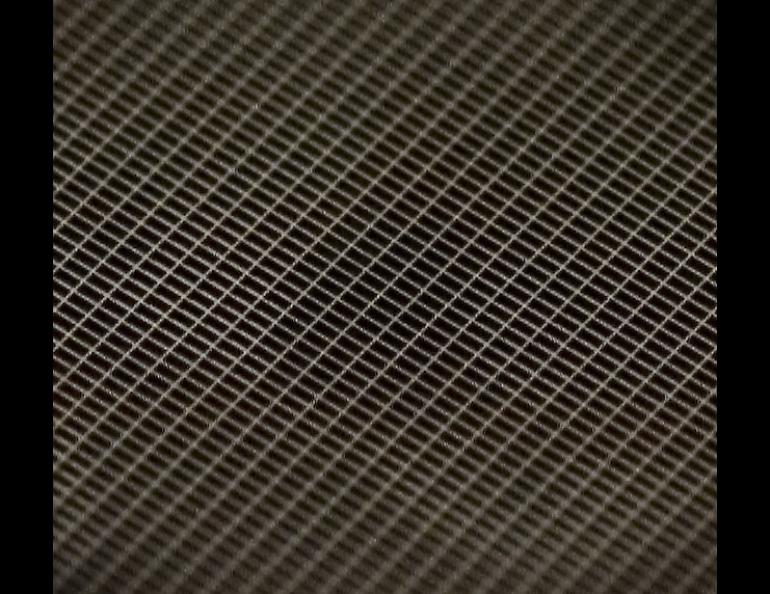

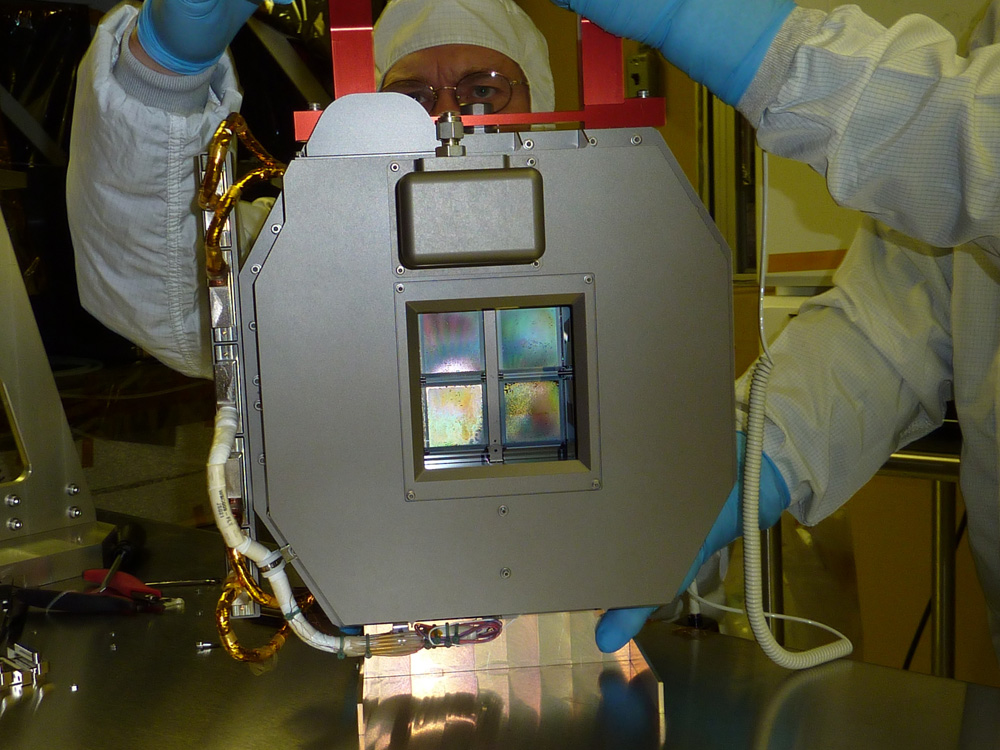

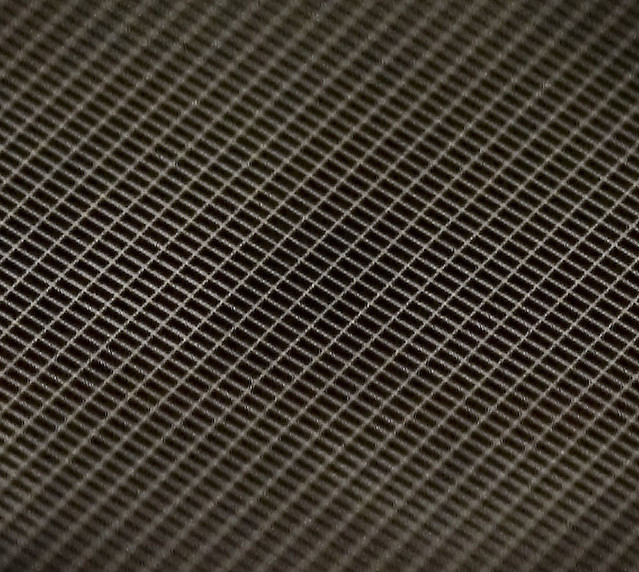

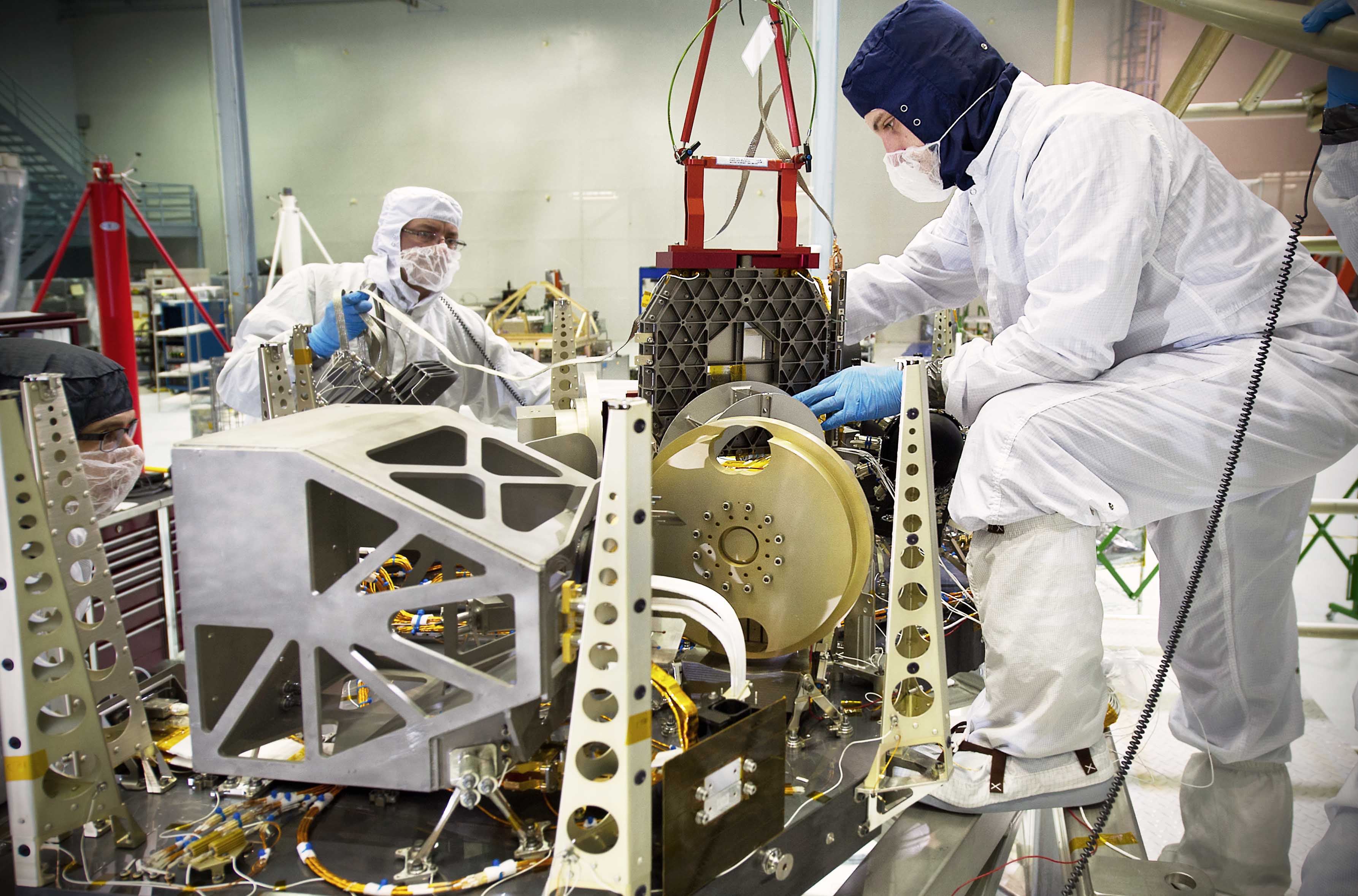

Kletetschka, an expert in magnetism, helped devise a mechanism to do something remarkable while working at NASA in the early 2000s: open and close any number of the 248,000 microshutters on the Webb telescope’s Near Infrared Spectrograph. That allows the telescope to acquire high-resolution images of up to 200 objects simultaneously without image clutter from other objects.

That ability is a first. NASA says it will allow for more scientific research to be conducted in less time.

“They decide on a pattern and which shutters they need to close,” Kletetschka said. “They are individually controllable.”

The microshutters are exceptionally small, measuring 100 microns by 200 microns. A hundred microns is the thickness of a standard sheet of paper in an office copy machine.

Think of each microshutter as a tiny lidless shoebox, with the bottom of the shoebox able to flip up and inward on its long side.

Infrared radiation passes through the open shutters to the instrument’s detector.

Magnetism is the key to operating the shutters, but NASA’s earlier attempts to use magnets to open and close the shutters didn’t work.

The mechanism that Kletetschka and colleagues at NASA came up with uses a slender bar magnet the width of each array. When directed to move across an array, the magnet opens all of the shutters in that array.

The shutter — the floor of the shoebox — flips up and is held against the sidewall of its own shoebox by a controllable electrostatic field separate from the magnet. With all of the shutters open, scientists back on Earth decide which shutters to close by releasing the electrostatic field holding that shutter open.

“They open all of the shutters and then close the ones they don't want so they can get the desired viewing pattern,” Kletetschka said.

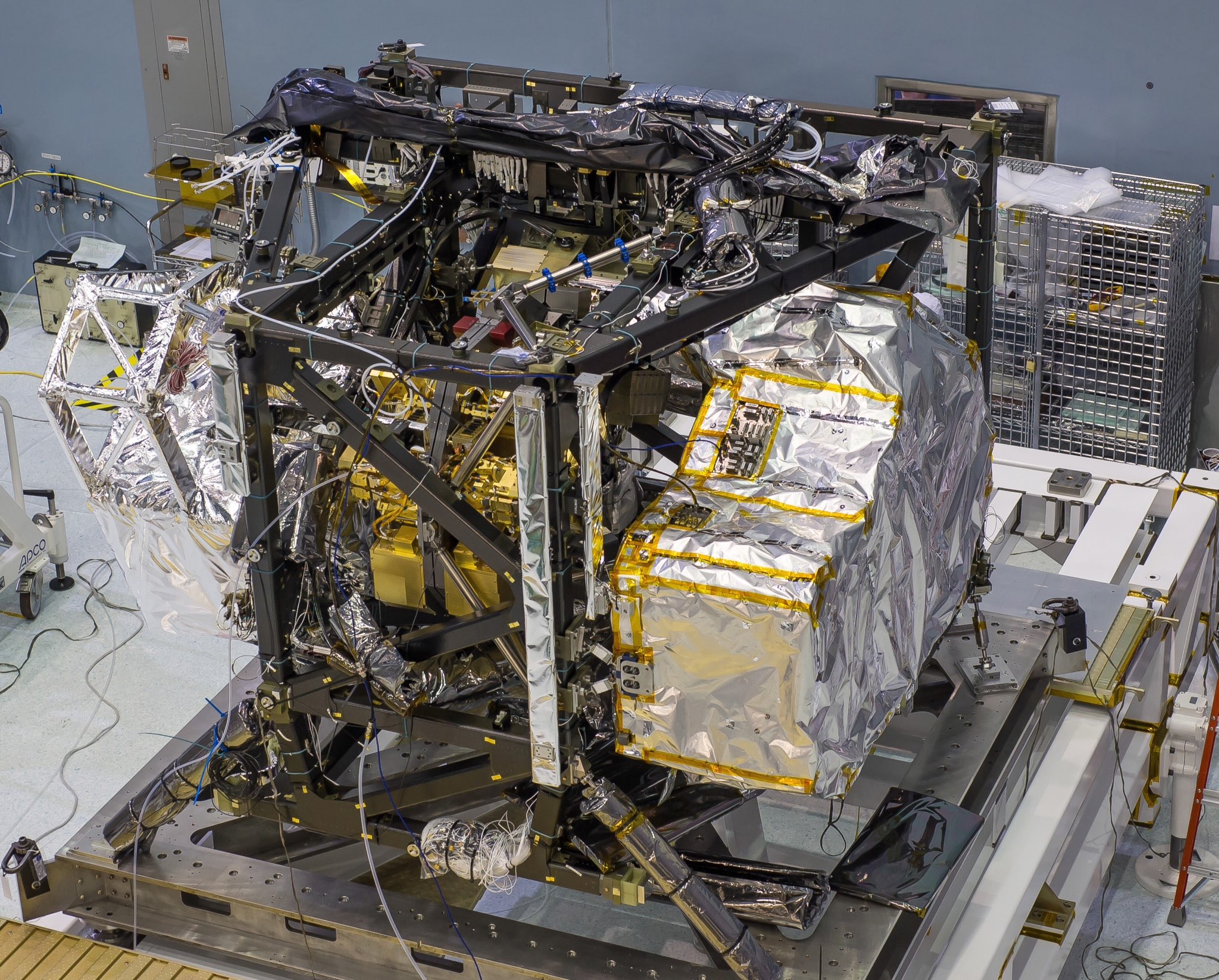

It’s also important to have a magnet that consists of the proper material to operate as desired in the cold of space.

That was a problem that Kletetschka sorted out. And it involved the difference of one proton.

Their first magnets used the rare-earth element neodymium in conjunction with iron and boron, a common combination for making supremely strong magnets.

It worked well at room temperature. The problem, though, was that the temperature aboard the telescope would be about 50 kelvins, or 370 degrees below zero. Testing the magnet by cooling it in liquid helium to 50 kelvins saw the neodymium magnet lose nearly all of its magnetism.

They needed a material to replace neodymium. The answer: praseodymium, a rare-earth element that has one proton fewer than neodymium.

The change prevented the loss of magnetism and actually provided a slight boost in the magnet’s strength.

“There was some kind of magnetic transition around that 50 kelvins temperature where there were two different electron spins that were fighting each other,” Kletetschka said. “That's why the neodymium was not practical for the telescope.”

The work on microshutters has inspired Kletetschka to propose creating an electrostatically propelled levitating platform that would serve as a means of studying the moon’s electrostatic field, which is caused by the solar wind. He is working on the idea with UAF doctoral students Joshua Knicely and Nick Hasson.

The Webb telescope is a partnership of NASA, the Canadian Space Agency and the European Space Agency.