Scientists aim to improve sea ice predictions' accuracy, access

Sea ice predictions have improved markedly since the founding of an international forecasting and monitoring network 14 years ago.

“These forecasts are quite encouraging in their increasing accuracy,” said Uma Bhatt, an atmospheric sciences professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute. Bhatt spoke about the Sea Ice Prediction Network at the American Geophysical Union’s annual meeting last month.

As the amount of sea ice in the Arctic declines, thins and becomes more mobile, accurate forecasts are becoming even more vital for things like fisheries and resource development, shipping, subsistence activities and wildlife management.

Bhatt said the SIPN team hopes to work with the Alaska maritime industry, especially the Bering Sea snow crab fishermen, to make ice forecasts even more accurate and useful to those who work in or live next to the world’s polar waters and to scientists studying sea ice decline and the Arctic climate.

The SIPN team plans to enhance sea-ice predictions by including data for sea-ice thickness, surface roughness, melt ponds, and snow depth; involve the public in climate and sea-ice prediction; and evaluate the socioeconomic value of sea ice forecasts.

“The computer models are continually being improved,” Bhatt said back in Fairbanks. “That is what researchers do: keep improving their models. The improvements are slow and steady, but you see it once you look at multiple years.”

What is SIPN?

The Sea Ice Prediction Network formed shortly after the then-record Arctic sea ice minimum of 2007.

“That really shocked some scientists and garnered a lot of public attention,” Bhatt said.

Sea ice outlook forecasts began the following year and continued through 2013 on minimal funding. The National Science Foundation began providing financial support in 2014, allowing the eventual inclusion of forecasts for Alaska and Antarctica.

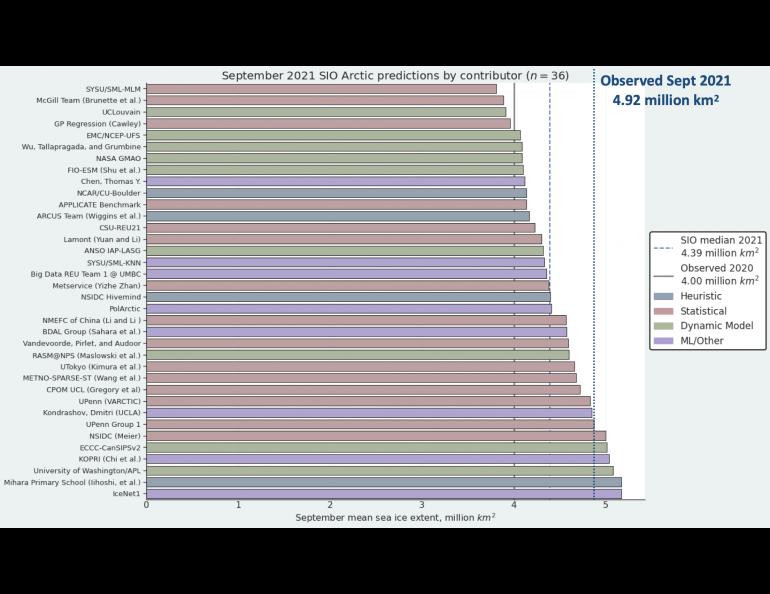

The network uses dozens of forecasts from a global community to provide September sea ice minimum forecasts in June, July, August and, finally, September, usually the month during which sea ice is at its lowest. The network also publishes the current extent for June, July and August.

A new phase, SIPN2, began in 2018 with National Science Foundation support for activities such as an analysis of sea ice maps, more analysis of forecasts and a socioeconomic component.

Bhatt is the project lead and principal investigator for the SIPN2 Project Team, which includes several members of the UAF International Arctic Research Center, including IARC Director Hajo Eicken.

“The sea ice outlook provides a unique opportunity for a diverse group to work together to seek common conclusions about seasonal sea ice forecasting, using multiple models and methods, and currently we're working on the next phase,” Bhatt said.

Getting better

Forecasters have been learning more about sea ice behavior and improving their forecasting.

Error percentage decreased notably from August to September in all forecast methods in 2021, the first year that September was included, and should continue to be low in the future, Bhatt said.

Improvement also has occurred in the geographic scope of the forecasts, which for five years have included the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas around Alaska. The data record is short, but the accuracy rate is good.

Sea ice forecasters from around the world don’t all use the same prediction model, a fact that has allowed for a comparison of results and methods — and, ultimately, a better forecast.

“Having been part of this effort since the start, it's great to see an international community grow around forecasting,” Eicken said. “The work of this team has increasingly focused on how to improve predictions that benefit Alaskans and other local groups in the Arctic.”

Some puzzles have popped up over the 14 years of the network’s existence. For example, the median June forecasts for the coming season correlate best with observations of the previous September. Researchers want to know why.

“So we are very good at forecasting the prior year,” Bhatt said, tongue in cheek.

What’s next?

The team may expand its forecasting into the winter months to address the needs of Bering Sea crabbers, a key part of Alaska’s multimillion-dollar seafood industry.

Joseph Little, a former economics professor in the UAF College of Business and Security Management and now an affiliate research professor at IARC, and others surveyed crabbers. They want information on sea ice location, extent, direction and concentration in winter and spring.

Bhatt said such forecasts would aid safety, route planning, navigation, resupply and fuel purchases.

Forecasters also continue to work with models to improve sea ice outlooks by understanding the influences, for example, of snow on ice and of melt ponds. They will also use a new data portal to look at potential bias such as a prediction being influenced by the observation of the prior year.

“Over the course of 14 years, the Sea Ice Prediction Network has strengthened and developed to highlight common features in seasonal sea ice forecasting,” Bhatt said. “SIPN is committed to fostering a network that synthesizes diverse thinking and continues to reduce the gap between sea ice forecasting and stakeholder needs.”

Bhatt’s AGU presentation is here.

Uma Bhatt, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-2662, usbhatt@alaska.edu

Rod Boyce, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-7185, rcboyce@alaska.edu

Heather McFarland, International Arctic Research Center, 907-474-6286, hrmcfarland@alaska.edu