Remembering Sergey Marchenko: Internationally known geocryologist

The Geophysical Institute lost a longtime member of its permafrost team last week with the death in Fairbanks of Research Associate Professor Sergey Marchenko, a recognized leader among the world’s geocryologists.

He was 61.

Marchenko became associated with the Geophysical Institute in 2003, when he began a three-year appointment as a visiting research scholar. He became a research associate at the conclusion of that period and in 2008 became a research associate professor, a position he held at the time of his death.

The funeral for Research Associate Professor Sergey Marchenko will be at 1 p.m. on Wednesday, July 10 at the Legacy Funeral Home on 415 Illinois St. The GI community is welcome to attend. If you'd like to support Sergey's wife Gulnara during this difficult time, please visit this GoFundMe created by Dmitry Nicolsky.He was affiliated with the Geophysical Institute’s Permafrost Laboratory and Snow, Ice & Permafrost Group.

Marchenko’s speciality was in modeling and mapping permafrost, particularly in Alaska. He was also developing permafrost maps for the Tien Shan mountains, a major range in Central Asia that stretches across Kyrgyzstan, China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. It is known for its high peaks, glaciers and historical significance as part of the Silk Road.

He also studied permafrost of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, located in southwestern China. It is Earth’s highest and largest plateau and is known as the “Roof of the World.”

“Changes in permafrost lead to changes in everything — hydrogeology, topography, ecosystem, vegetation. Everything!” Marchenko said in a January 2020 Geophysical Institute news release about research he had presented a month earlier at the annual American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

Marchenko’s research areas of interest included climate-permafrost interactions and the influence of permafrost on landform and landscape development in Arctic, sub-Arctic and mid-latitude alpine environments; mountain permafrost formation, evolution and distribution throughout the Quaternary Period and into the future; and numerical modeling of permafrost dynamics and spatial analysis. He also developed high-performance computing models.

He authored or co-authored approximately 80 peer-reviewed publications and made more than 110 presentations at international and national events since 2003.

Professor Emeritus Vladimir Romanovsky, who retired in 2022 after 30 years as a permafrost scientist at UAF, said his former permafrost colleague had an array of skills that made him unmatched.

“He had a very good combination of knowing the subject — permafrost and its physical processes — and the skills of modeling. And that’s what he was mostly working on at the Geophysical Institute, developing permafrost models. We worked together on that. He was very good.

“He also was good in mountain permafrost, because not many people, especially in the United States, are interested in mountain permafrost,” he said. “He was very, very knowledgeable in mountain permafrost. This combination made him a unique scientist.”

Romanovsky first brought Marchenko to UAF in 2000 with an invitation to a workshop on the thermal state of permafrost.

“It was the first international workshop on this,” Romanovsky said. “I was organizing it, and I chose him from his field of research.”

Romanovsky had met Marchenko in the 1980s, when Marchenko visited Moscow State University as a graduate student from a permafrost institute. Romanovsky was an associate professor teaching a course for visiting students.

Marchenko’s death brought condolences to the Geophysical Institute from China, where Marchenko had visited several times and had a relationship with the Chinese Academy of Sciences since 2011. He was a visiting professor at the academy’s State Key Laboratory of Frozen Soils Engineering, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources.

“This is a great loss to the GI and the permafrost community across the world,” reads the letter by eight academic permafrost scientists and engineers.

“Sergey is one of the best geocryologists in the world, with great depth of understanding in permafrost science and technology. He is one [of] the best-informed and most extensively traveled geocryologists in the world, with a comprehensive understanding of alpine, boreal and Arctic permafrost.

“Along these trips, he educated and advised us and our students with his profound knowledge of permafrost and professional teaching skills…,” it reads. “Because of his teaching and advice, some of us are able to achieve substantial progress in alpine and plateau permafrost research. His publications on northern and alpine permafrost are still educating many geocryologists and students.”

Immediately prior to joining the Geophysical Institute, Marchenko was senior scientist at the Kazakhstani Alpine Permafrost Laboratory at Yakutsk Permafrost Institute — now the Melnikov Permafrost Institute — of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences for 10 years.

He previously worked as an engineer at the Yakutsk Permafrost Institute and as an engineer-programmer at the Research Institute of Mechanics in Kazakhstan.

Marchenko obtained his Ph.D. in geocryology and glaciology from Moscow State University in 2000 and his master’s in mathematical methods in geology from that university in 1991.

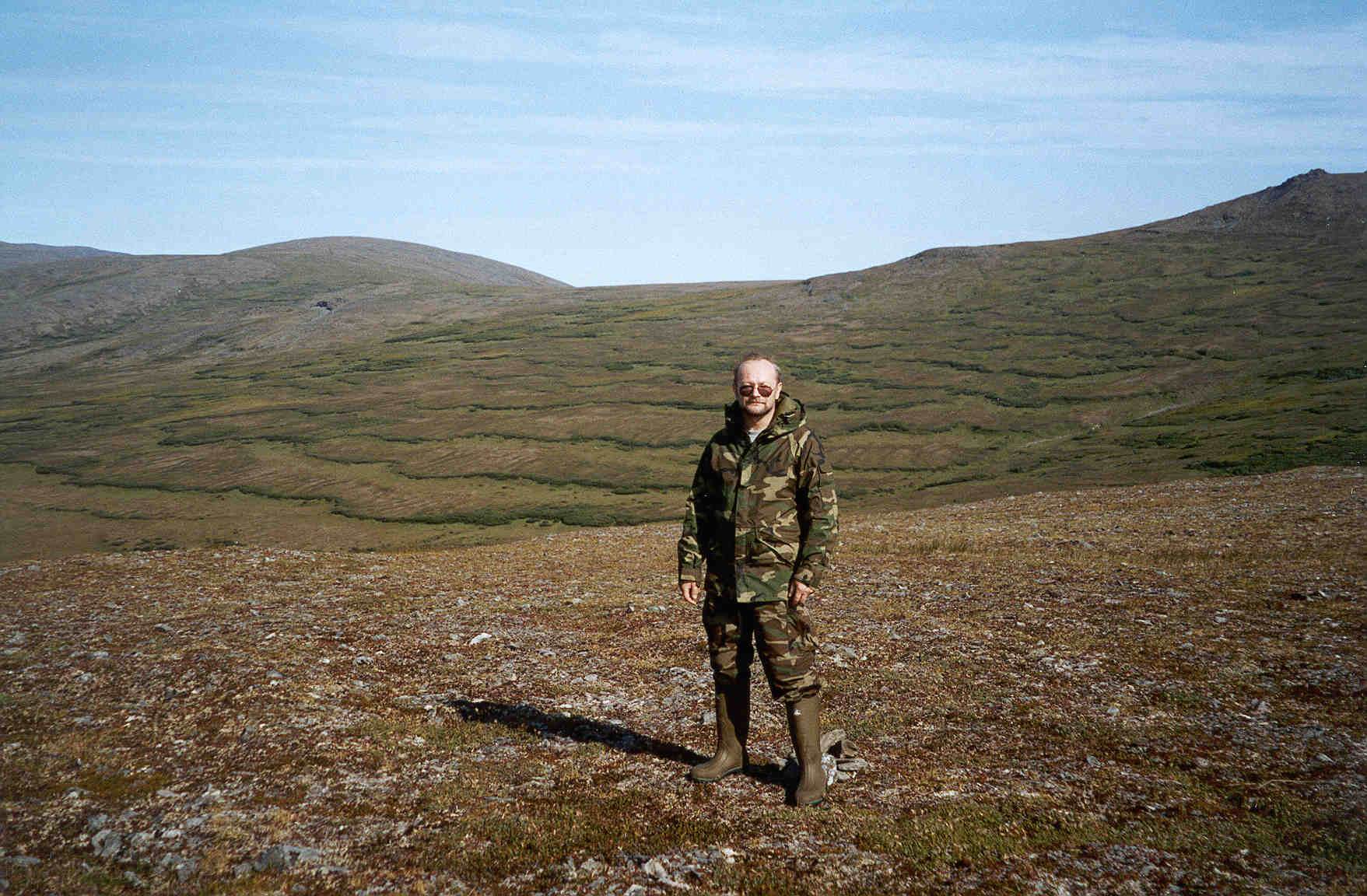

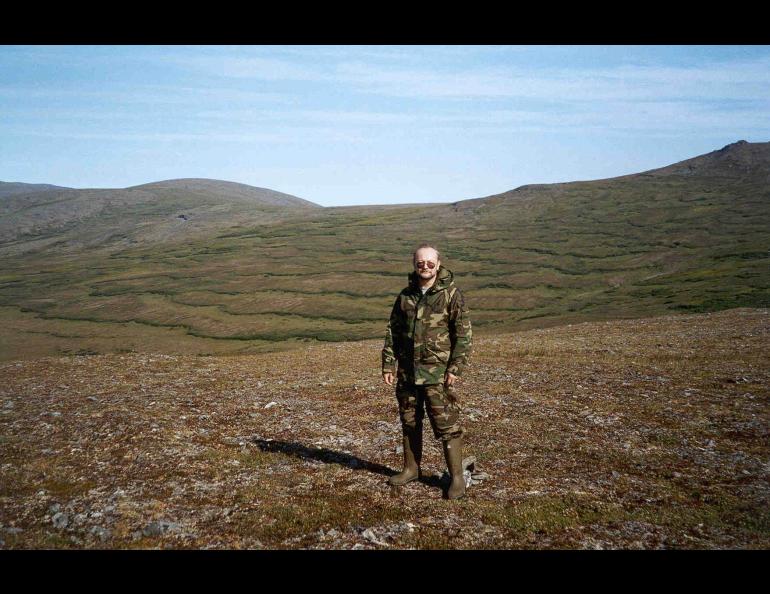

Marchenko had more than 30 years of fieldwork and expeditions, often as part of international efforts. He visited the inner and northern mountains of the Tien Shan range in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan and the Altai mountains, which span Russia, Kazakhstan, China and Mongolia.

In Alaska, his research took him to the Brooks Range, Alaska Range, Ivotuk Hills of the North Slope, Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve in Interior Alaska and Seward Peninsula.

Marchenko presented his most recent work at the International Conference on Permafrost, held in Whitehorse, Yukon, in mid-June of this year. That poster was titled “Estimation rates of permafrost degradation and their impact on ecosystems across Alaska.”

It was produced with Geophysical Institute colleagues, including Romanovsky and Research Associate Professor Dmitry Nicolsky, a colleague of Marchenko’s in the Geophysical Institute’s Permafrost Laboratory.

“He was proud of that poster. It was summarizing all of his work,” Nicolsky said.

“He was helpful and was always offering assistance. If you asked him questions, he would be welcoming,” he said. “He was a quiet human, a humble person, but he liked good jokes.”

Marchenko was born in the Kazakhstan city of Alma-Aty, now Almaty. Today it is a city of approximately 2 million in the foothills of the Trans Ili-Alatau mountains.

Outside of his professional life, Marchenko enjoyed fishing, both freshwater and saltwater, and ice fishing, according to colleagues.

“He really liked that,” Romanovsky said. “Yes, he really liked it.”

- Rod Boyce, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-7185, rcboyce@alaska.edu