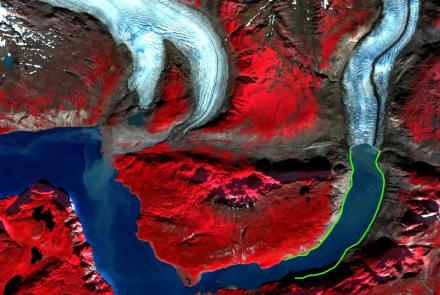

Study to investigate melting Malaspina Glacier, potential new bay

The rapidly melting Malaspina Glacier in southeastern Alaska’s Wrangell-St. Elias National Park could create a new ocean bay, one feature in what may be the largest landscape transformation underway in the United States.

To better understand these changes, the National Science Foundation recently awarded researchers from the University of Alaska Fairbanks and two partner institutions a $1.3 million grant to study its retreat.

The Malaspina is a piedmont glacier, a valley glacier that flows onto lowland plains. It’s the largest of its kind in the world — larger in area than Rhode Island — and it’s melting fast.

The researchers will collect comprehensive data on ice velocity and thickness, glacier bed conditions and other features to characterize the glacier under possible future climate scenarios. Scientists will use the data to create thousands of computer models to predict these outcomes under various conditions.

Martin Truffer, a professor of physics at the UAF Geophysical Institute, is the primary investigator on the project, which includes GI researchers Chris Larsen and Mark Fahnestock. Researchers from the University of Montana (including Doug Brinkerhoff, a former UAF graduate student co-advised by Truffer), the University of Arizona and the National Park Service will collaborate on the project.

According to Truffer, melting of the Malaspina could open up a new bay in the coastline of Alaska within this century, altering the entire local ecosystem.

Truffer compared this landscape change to neighboring Yakutat Bay, which was full of ice from the Hubbard Glacier about 1,000 years ago. Hubbard retreated over a span of about 800 years, opening up Yakutat Bay. Hubbard’s loss was similar to the volume of ice the Malaspina stands to lose.

The melting of Malaspina could have significant impacts outside Alaska, too.

“Over the next few decades, a lot of what we’re seeing in terms of sea level rise is largely influenced by nonpolar ice,” Truffer said. “Alaska is near the very top of contributors, and, in Alaska, the Malaspina is one of the largest contributors.”

The Malaspina Glacier “comes spilling out of the St. Elias Mountains onto this coastal plane and looks like a pancake,” said Truffer. “It’s really an unusual glacier because it has so much ice at a low elevation.”

Its location makes the Malaspina especially vulnerable to an accelerated cycle of melting. As the ice melts, it comes into contact with more water, which speeds up the process. However, the ice can’t retreat out of the water because the bottom of the ice is so low, at some points 1,000 feet below sea level. This causes the Malaspina to thin rapidly, in some places several yards a year.

“It’s probably some of the largest change we can expect anywhere in Alaska, maybe anywhere in the world,” Truffer said.

The project will include efforts to better understand how the public interprets information about these changes. A graphic designer will convert scientific results from computer-generated models into realistic visuals to educate visitors at Wrangell-St. Elias National Park about how the landscape might change over the next 50 years.

Kristin Timm, a postdoctoral researcher at the UAF International Arctic Research Center, will investigate how changes in glaciers affect the ways humans understand our environment.

“When we see news or information about climate change, it’s not uncommon to see photos of a glacier 30 or 50 years ago and what it looks like today or a dramatic video of a glacier calving into the water,” Timm said. “However, we don’t really know if images like that cause people to feel hopeful or hopeless about our ability to respond to human-caused climate change.”

Fritz Freudenberger, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-7185, ffreudenberger@alaska.edu