UAF scientists discover phenomenon impacting Earth’s radiation belts

Two University of Alaska Fairbanks scientists have discovered a new type of “whistler,” an electromagnetic wave that carries a substantial amount of lightning energy to the Earth’s magnetosphere.

The research is published today in Science Advances.

Vikas Sonwalkar, a professor emeritus, and Amani Reddy, an assistant professor, discovered the new type of wave. The wave carries lightning energy, which enters the ionosphere at low latitudes, to the magnetosphere. The energy is reflected upward by the ionosphere’s lower boundary, at about 55 miles altitude, in the opposite hemisphere.

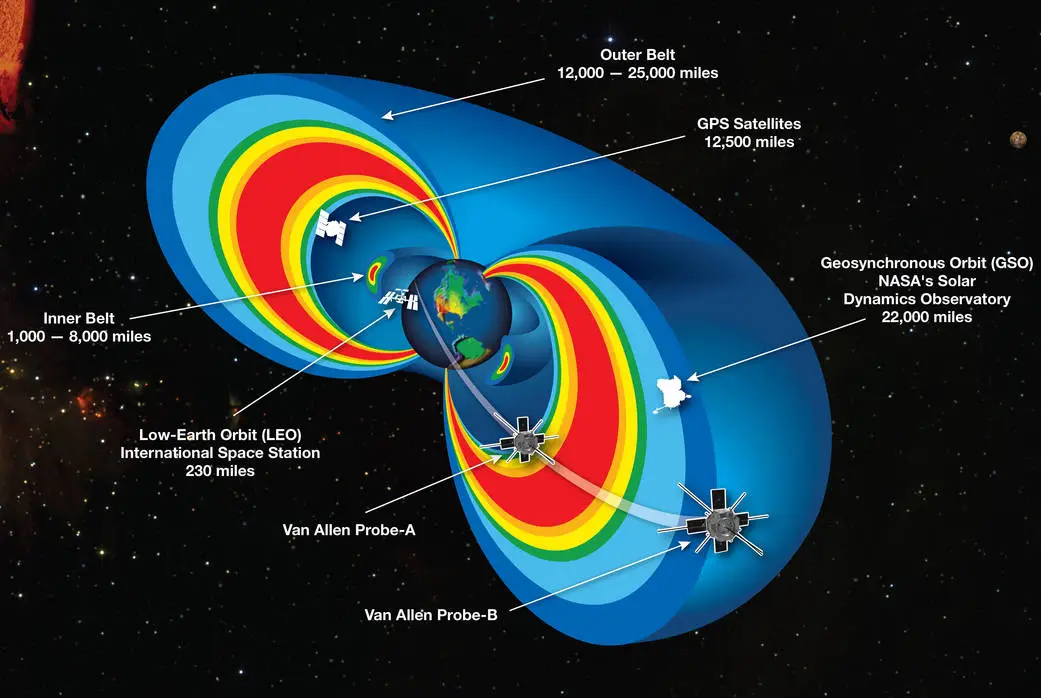

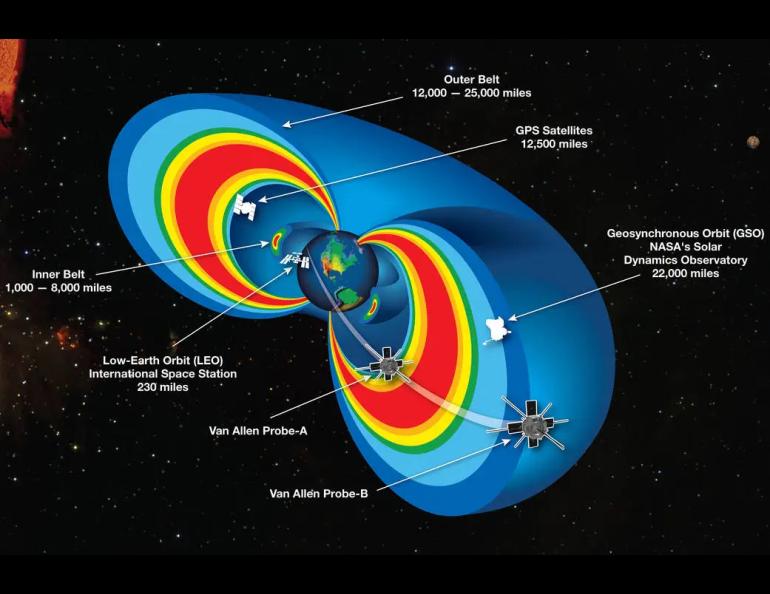

It was previously believed, the authors write, that lightning energy entering the ionosphere at low latitudes remained trapped in the ionosphere and therefore was not reaching the radiation belts. The belts are two layers of charged particles surrounding the planet and held in place by Earth's magnetic field.

“We as a society are dependent on space technology,” Sonwalkar said. “Modern communication and navigation systems, satellites, and spacecraft with astronauts aboard encounter harmful energetic particles of the radiation belts, which can damage electronics and cause cancer.

“Having a better understanding of radiation belts and the variety of electromagnetic waves, including those originating in terrestrial lightning, that impact them is vital for human operations in space,” he said.

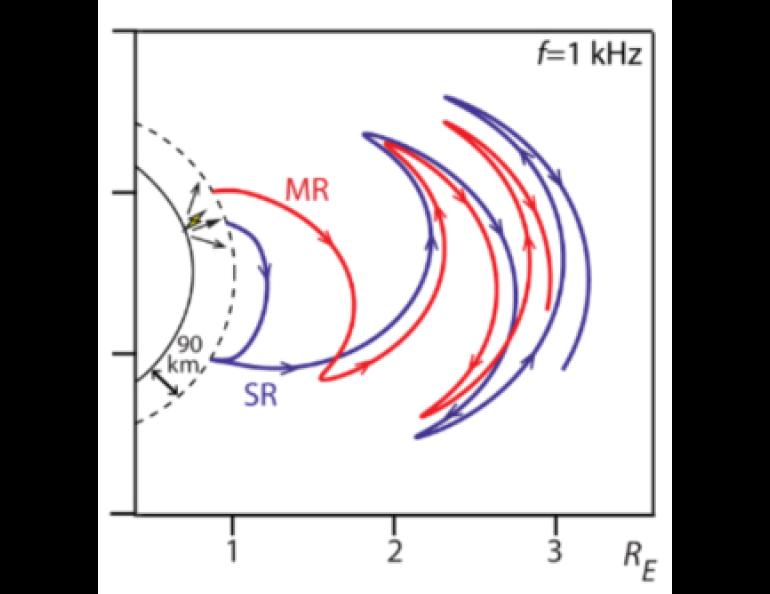

Sonwalkar and Reddy’s discovery is a type of whistler wave they call a “specularly reflected whistler.” Whistlers produce a whistling sound when played through a speaker.

Lightning energy entering the ionosphere at higher latitudes reaches the magnetosphere as a different type of whistler called a magnetospherically reflected whistler, which undergoes one or more reflections within the magnetosphere.

The ionosphere is a layer of Earth's upper atmosphere characterized by a high concentration of ions and free electrons. It is ionized by solar radiation and cosmic rays, making it conductive and crucial for radio communication because it reflects and modifies radio waves.

Earth's magnetosphere is a region of space surrounding the planet and created by Earth's magnetic field. It provides a protective barrier that prevents most of the solar wind's particles from reaching the atmosphere and harming life and technology.

Sonwalkar and Reddy’s research shows that both types of whistlers — specularly reflected whistlers and magnetospherically reflected whistlers — coexist in the magnetosphere.

In their research, the authors used plasma wave data from NASA’s Van Allen Probes, which launched in 2012 and operated until 2019, and lightning data from the World Wide Lightning Detection Network.

They developed a wave propagation model that, when considering specularly reflected whistlers, showed the doubling of lightning energy reaching the magnetosphere.

Review of plasma wave data from the Van Allen Probes showed that specularly reflected whistlers are a common magnetospheric phenomenon.

A majority of lightning occurs at the low latitudes, which are tropical and subtropical regions prone to thunderstorm development.

“This implies that specularly reflected whistlers probably carry a greater part of lightning energy to the magnetosphere relative to that carried by magnetospherically reflected whistlers,” Sonwalkar said.

The impact of lightning-generated whistler waves on radiation belt physics and their use in remote sensing of magnetospheric plasma have been researched since the 1950s.

Sonwalkar and Reddy are with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering in the UAF College of Engineering and Mines. Reddy is also affiliated with the UAF Geophysical Institute.

Sonwalkar and Reddy’s research is supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and NASA EPSCoR, the Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research.

• Vikas Sonwalkar, University of Alaska Fairbanks vssonwalkar@alaska.edu

• Rod Boyce, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-7185, rcboyce@alaska.edu