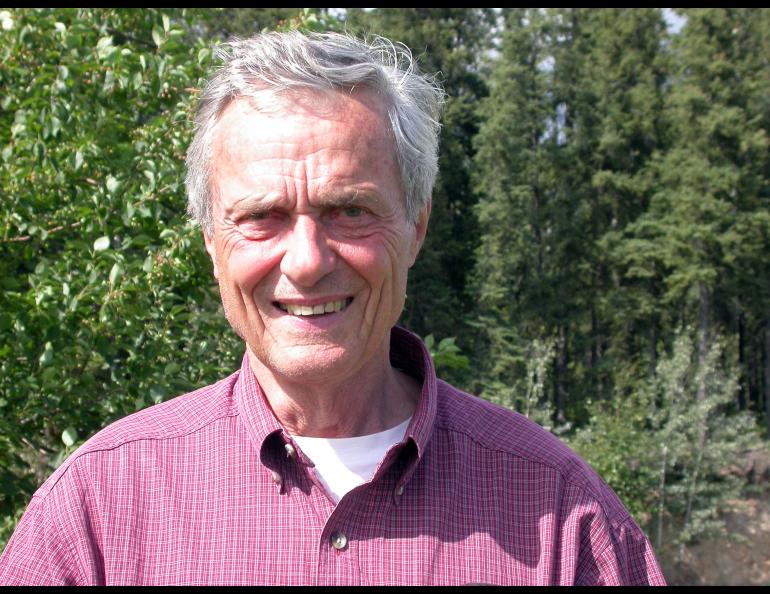

Biologist sees value in unchanged landscape

George Schaller has studied gorillas in Rwanda, lions on the Serengeti, pandas in China, antelope in Tibet, and many other animals in wild places around the planet, but he thinks the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is unique among them. He visited there in 2006 for the first time in half a century.

“On the Sheenjek (River), we climbed the same cliff I climbed in 1956, and looking out there was no difference—no roads, no buildings, no garbage dumps.

“I’m sure there are rain forests in Brazil where you can walk for a few days without seeing people or big changes to the landscape, but sites like (the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge) that are ecologically whole are extremely rare.”

Schaller, possibly the most recognized biologist in the world, traveled to Alaska seven summers ago from his home in Connecticut for a trip through the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge with author Jon Waterman, University of Alaska Fairbanks students Betsy Young and Martin Robards, Forrest McCarthy from the University of Wyoming, and Gary Kofinas of UAF. Most of the group drove the Dalton Highway to Deadhorse, took a trip down the Canning River by raft, and then flew to Arctic Village and the upper Sheenjek River. Schaller had not been to the latter two places in 50 years, since he joined biologists and naturalists Olaus and Mardy Murie and others on a trip there that resulted in the creation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

“We went almost to the same spot as 50 years ago,” he said while in Fairbanks after his trip. He began his academic career at UAF in the 1950s, studying biology and living in a tent on campus, a pet raven his occasional companion.

Schaller carried photos from his 1956 trip with him on his 2006 Alaska journey.

“The wonderful part was the timelessness of the landscape,” he said. “I identified spruce trees that were the same, and an eagle’s nest at a limestone cliff was still there.”

After his wilderness trip, Schaller, now 80, headed from Fairbanks back to the East Coast for a few days at home with his wife Kay. From there he would fly to Iran, where he has tracked the rare Asian cheetah. Before he left Fairbanks, he said the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge should remain untouched.

“As a naturalist, it’s important from a scientific point of view to have an area that hasn’t been degraded, where all parts of the ecosystem are still there,” he said. “If you don’t have a place to compare things to, you don’t know what it used to be like.

“Also, it’s nice to have a place that lets you feel like what it was like to live in the past, as if you’re Lewis and Clark,” he said. “A lot of people in this hectic world need silence on a spiritual level. Most religious prophets would seek out the wilderness . . .

“Animals and plants have a right to exist, too,” he said. “We don’t have to destroy them for short-term goals. Ultimately, our quality of life depends on a healthy environment, and for a healthy environment we need open space.”