Traveling through time in the Alaska bush

TOLOVANA ROADHOUSE — On the dark, frozen white plain of the Tanana River, a white dot appeared in the night.

It was the headlamp of Ryan Redington, a dog musher in the 2025 Iditarod race, the start of which officials moved from Willow to Fairbanks because of low snow conditions.

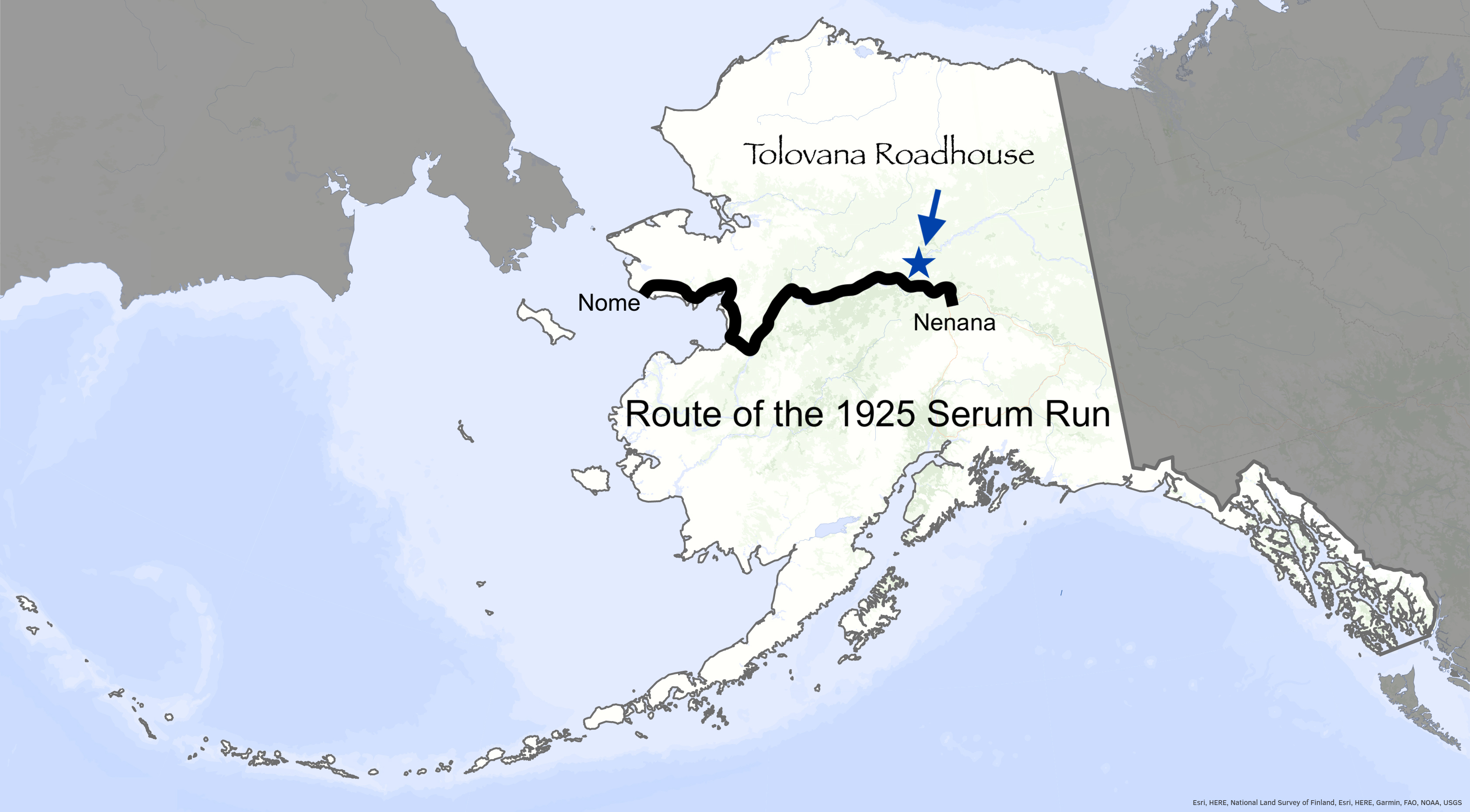

The re-routed trail followed the frozen Chena River for a few miles in Fairbanks before merging with the much wider Tanana. From there it led about 50 miles to Nenana, then through frozen swamps and over wooded portages to Tolovana Roadhouse.

This place, 100 yards east of where the Tolovana River in summer dumps its brownish water into the Tanana, includes an unusual structure in this country of log cabins small enough that most people need to duck to avoid bumping their head.

The Tolovana Roadhouse has burned to the ground a few times. This version — canary yellow and 80 feet long — was built in 1924. That was just in time to provide shelter for a musher on the first leg of relaying a diphtheria antidote from Nenana to Nome. The event came to be known as the Serum Run of 1925. One century later, the dogs returned to Tolovana Roadhouse.

At 1:30 a.m. on March 4, 2025, Mary Knight, a Fairbanks nurse and dog musher, stood out on the snow-covered ice in front of the roadhouse. She had purchased the structure and the land five months before.

She paced in her heavy winter boots, waiting for the first of 33 dog teams. Tolovana Roadhouse was not an official Iditarod checkpoint. Officials called it a “hospitality stop.”

A breeze from the north carried sweet, heavy spruce smoke down to the river. It was the product of five cast-iron wood stoves on the property — three in the expansive main lodge; one from a barn and another from a sauna that held two 50-gallon barrels of river water from a hole chopped in the ice. The water was a service provided to all of the mushers; they would warm it in cookers fired by bottles of Heet and feed their dogs stews of kibble, beaver meat and other high-fat items.

Across the river — beyond where Knight shifted from foot to foot — two great horned owls hooted nonstop.

Redington’s headlight grew brighter until he stepped on his brake as he reached Knight, jabbing points into the snow between his sled runners.

“Welcome to Tolovana Roadhouse,” Knight told him. “Take your dogs up the bank and people will help you park your team if you are staying.”

“I am,” Redington said.

“Great,” Knight said. “There’s water in the sauna, and lots of food inside and a bunk for you when you finish your chores. Outhouse is the large building behind the roadhouse.”

Redington pulled his snow hook. His dogs trotted up the ramp of snow to the several-acre flat upon which the roadhouse sits. A dog handler working for Knight ran in front of the 16-dog team and stopped by the sauna.

Redington stepped off his sled, a heavy green parka weighing him down, and petted each of his dogs, their muzzles coated in frost.

As the dogs settled on patches of straw Redington sprinkled from a bale he had carried from Nenana on his sled, a boreal owl sang its spooky song from the nearby woods. Overhead, the northern lights flickered to life, a faint green oval.

Except for the satellite internet connection with which Knight and her helper friends were tracking the mushers, the scene at Tolovana Roadhouse was pretty close to what it might have been in 1925.

Back then, on a February night that was at least 40 degrees colder than the 0 degrees Fahrenheit in 2025, Wild Bill Shannon mushed into the roadhouse with his vials of diphtheria serum wrapped in furs. The 1925 Serum Run team of 20 mushers relayed that antidote 674 miles to Nome in 5-and-one-half days.

During a few March nights and days in 2025, dog mushers in the Iditarod race were on a journey that would last two weeks or more. Knight and her friends had wondered how many mushers would opt to rest at Tolovana Roadhouse for a few hours and how many would mush on by.

She was surprised that almost every musher opted to stop. At the peak of the action, 17 teams were parked in parallel lines of dogs resting on straw surrounding the roadhouse and its outbuildings. Kyler Kuntz, Knight’s hired dog handler from Washington, sweated through his layers as he led teams from the river to their parking areas.

For a few March nights, the only surviving structure from the 1925 Serum Run once again hosted a snoring musher (many of them) and provided a place of rest during a journey across the width of Alaska.

Iditarod musher Jenny Roddewig of Two Rivers pondered the significance of a snowless southern portion of the Iditarod Trail as she warmed water for her dogs close to the eroding bluff of the Tanana River.

“I believe things happen for a reason,” she said.