Expansion of permafrost tunnel planned

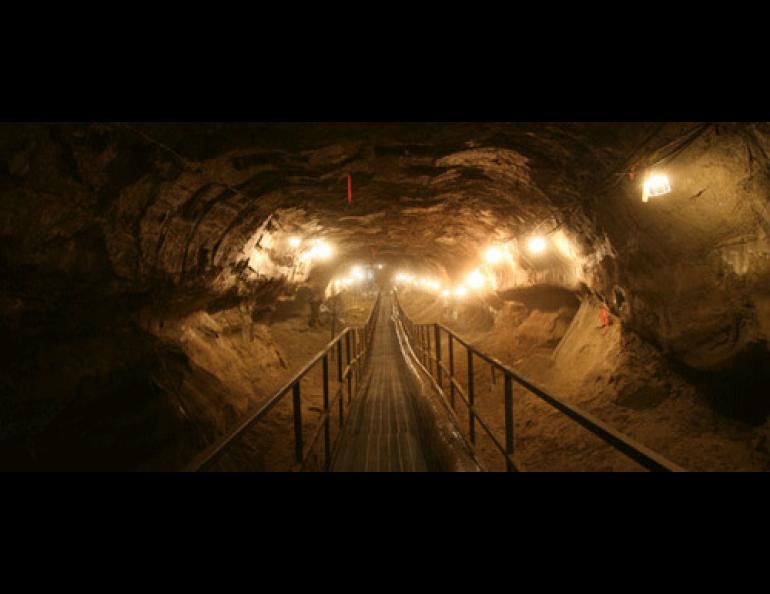

Researchers plan to expand the Fox Permafrost Tunnel during the next few years, drilling or blasting a new shaft 450 feet into a frozen hillside to parallel the existing tunnel.

“We want to begin digging (a new) permafrost tunnel next winter,” said Matthew Sturm of the U. S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory on Fort Wainwright. He and others envision a new “Alaska Permafrost Research Center” that will better serve scientists and non-scientists.

With start-up federal funding of $500,000 this year, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will carve out a new tunnel as well as build labs, offices, and a learning center. Other improvements include a walkway on top of the frozen bluff where scientists can do permafrost experiments from the forest and tundra above the tunnel, and side rooms within the new tunnel for permafrost-warming experiments. The improvements would replace infrastructure at the tunnel that has endured for four decades.

“Our current on-site facilities consist of a shack and a Porta-Potty,” Sturm said.

The new tunnel would be excavated during the winter of 2010-2011 with a “road header” or by drilling and blasting, whichever method is found to best preserve large chunks of permafrost that could include animal and plant remains, said Kevin Bjella of the Corps of Engineers.

The Corps Engineers dug the original tunnel 360 feet into a frozen hillside exposed by miners as they blasted a hillside with water from a hydraulic giant in the northern Goldstream Creek valley, about 15 miles north of Fairbanks. The engineers used an Alkirk mining machine with a pair of spinning six-foot cutting heads to create the tunnel during three winters from 1963 through 1966.

The official reason the Army dug the tunnel in the 1960s was to test ways of digging into permafrost and learn more about building underground usable spaces and foundations in permafrost. Near Thule Air Force Base in Greenland, the military dug ice tunnels hundreds of feet long with rooms for people to live and work.

“We have a permafrost tunnel because of Cold War fear,” Sturm said at a lecture on the tunnel expansion.

Since it opened in the late 1960s, the tunnel has lured scientists who have written more than 70 papers on their studies conducted within. Richard Hoover, a microbiologist with National Aeronautics and Space Administration, raved about the tunnel’s potential to show how life can exist on extreme places like Mars. He had scraped some ice from the bottom of a frozen lake, and he brought the ice back to a University of Alaska Fairbanks lab to look at what he suspected were samples of algae from the pond. Instead, he discovered rod-shaped bacteria that swam around on his slide. They were unknown to science and had been in suspended animation since the time of the woolly mammoth.

“This unique microorganism was alive after remaining frozen for 32,000 years,” he wrote in a paper.

The existing tunnel smells sour from the plants and animals decaying from their first exposure to the atmosphere in thousands of years. Researchers have found the preserved remains of ancient beetles, mites, flies, moths, butterflies, snails, and bones and teeth of mammoths, bison and horses within the tunnel. Also inside the tunnel are roots of willows, birches and alders, though no black spruce, which made their way to Alaska less than 10,000 years ago. The current tunnel, penetrating 65 feet of permafrost between the top of the hill and bedrock, has frozen material from 10,000 to 40,000-years-old, caused by extreme cold that penetrated the ground during those frigid years. Back then, tundra and shrubs were probably the dominant vegetation in the area, walked upon by horses, mammoths, and bison.

If things go according to plan, the new tunnel could open in 2013, and should be more accessible for researchers and others curious about permafrost, Sturm said.

“I think, in the end, more of the public will be able to use this,” Sturm said. “It’s a nice legacy project. The last tunnel is a gift that’s been giving for 50 years.”