Girls on the ice of Alaska

This summer, the Girls on Ice program visited an Alaska glacier for the first time. It probably won’t be the last, said organizer Joanna Young.

“We talked about how the girls would be inspired, but we didn’t count on how much we would be inspired,” said Young, a graduate student in the College of Natural Science and Mathematics at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. In July, she, two other grad students, and a mountaineer led nine teenage girls onto Gulkana Glacier for eight days of science and life on ice.

The Girls on Ice program, the creation of Alaska glaciologist Erin Pettit, has existed for more than a decade on the glaciers of Washington. Pettit, an assistant professor with the College of Natural Science and Mathematics, expanded the program this year to include Alaska, entrusting the details and organization to Young and fellow graduate students Barbara Truessel and Marijke Habermann. One of their first tasks was to choose an Alaska glacier for the program. They decided on the Alaska Range’s Gulkana Glacier.

“It was the perfect spot,” Young said. “We all knew the glacier well, it’s road accessible, it’s got this Indiana Jones bridge and it’s safe — there’s no huge crevasses.”

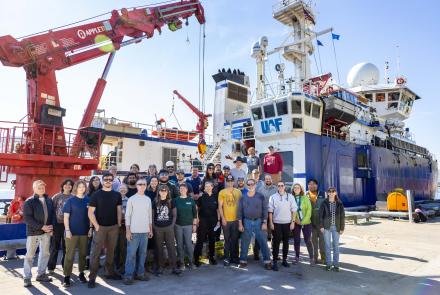

The trio of instructors, along with Cecelia “CeCe” Mortenson, who was fresh off a guiding trip on Mount McKinley, walked nine girls from Alaska and Washington over a footbridge, four miles up boulders and into a base camp they set up on rocks next to the glacier. Most of the girls had never worn plastic boots, crampons, or a 50-pound backpack. The 15-to17-year-olds faced physical and mental challenges they never imagined.

“The moraine’s rocky, unstable side was not the best landscape for me to be on,” said 18-year-old Heather Gregory of Anchorage of her initiation to the program. “I’ve never felt so scared to tumble down a hill before! But thankfully the instructors were there to calm me down and guide me through the moraine.”

Another participant, 16-year-old Chloe Smith of Palmer, said via email: “The hard part was facing the things that scared me or intimidated me, and the things that made me uncomfortable. Walking over a rickety suspension bridge. Carefully stepping over crevasse after crevasse as you were engulfed in wind, rain, and fog. Listening to the thunder and distant rock slides from inside our three small tents. I told myself, ‘You can do this. Even if it’s scary, you know you can. Think of how you’ll look back immediately after and say I did that.’”

Smith and her new friends impressed their instructors by their unwavering support of one another and their enduring a few days of rain with nowhere to escape except their tents.

“I was amazed at how nicely they interacted,” said Habermann, who models a Greenland glacier for her graduate work.

“They were so supportive of each other, and really kind to each other,” Young said of the girls. “They were so respectful of us as instructors. It was an opportunity for them to grow a lot and be like adults, and they took it.”

The girls performed science on the glacier, choosing studies on glacier ecology, the effects of rocks and dirt on glacial melt or water discharge from the streams on the glacier. After returning to Fairbanks, the girls gave presentations on what they learned at the university. And they experienced a transformation typical of girls who have attended the intense program on Washington glaciers.

“Before Girls on Ice, mountains were just mountains. Valleys were just valleys. Now when I see them they’re full of questions and stories,” Smith said. “Girls on Ice encouraged a new kind of curiosity in me about things I would have thought boring before. Now I’m considering to pursue geology after high school.”

“I liked the living-on-a-glacier part because being on the head of the glacier made you feel like Queen of the Valley,” Gregory said. “We also had makeshift classrooms in the tents, and the learning-then-discussions-after were really fun too.”

One of Smith’s favorite memories of the program is when another girl returned to camp with a tube of greenish glacier mud. That evening, the girls and instructors applied mud facials to one another, laughing and snapping photos.

“We’re out on the glacier, but we’re still girls,” Truessel said.

The instructors, busy trying to complete their own degrees, found the added stress of conducting a school for girls was one of the most rewarding parts of their graduate school experiences so far.

“I learned about grant writing, organizing a huge expedition, covering all the legal stuff and teaching science to girls who have no background in it,” Young said.

“Marijke and I have fantasized about having something like this in Switzerland when we’re back there,” said Truessel, who like Habermann is from Switzerland.

Girls on Ice is free for the high-schoolers, which means that its organizers have to raise all the funds to keep the program alive (this year’s sponsors included the Alaska Climate Science Center, the National Science Foundation, UAF’s College of Natural Science and Mathematics, the North Face and private donors).

Even though they have much work ahead in order to graduate, Young, Truessel and Habermann said they will do what they can to help create a 2013 Alaska version of Girls on Ice.

“It’s just worth it,” Young said.

The Alaska Science Forum has been provided as a public service by the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the UAF research community since the late 1970s. Ned Rozell is a science writer at the institute.