Life inching its way back to Kasatochi

In the mid-Aleutians, 1,200 miles from Anchorage, little Kasatochi Island—about 1.5 miles from end to end—was the surprise volcanic eruption of 2008, blowing up and painting itself in a shade of gray. Scientists revisited the island a few times in summer 2009 to see what, if any, life had returned. Here’s a report from the most recent trip; a few scientists and I returned from Kasatochi in mid-August.

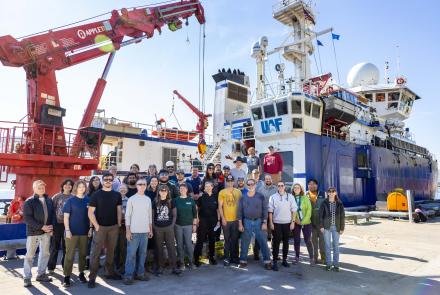

The crew of the Tiglax, the Alaska National Maritime Wildlife Refuge’s fine and functional 120-foot vessel, anchored a few hundred yards off the gray beach of the gray island and ran a skiff ashore with scientists dressed in orange Mustang survival suits. The weather was as colorless with the island, with moody clouds hiding the gaping crater rim at Kasatochi’s summit. In our three visits to the island, which were wedged between trips to calm bays of other islands, we would never see the top of Kasatochi.

No one hiked to the caldera, either, because the hiking was not good. The staggering tonnage of material spewed from the caldera covered the island like frosting on a gritty cake, and was less cohesive than pudding in many places.

The eruption had transformed the island from a dome sliced by cliffs into soft beaches that sloped lazily into the sea. With no vegetation to hold them in place, those slopes are now cut with deep gullies that have appeared since the crew of the Tiglax and scientists visited in June. Kasatochi in August 2009 was more like the moon than its former self.

Seen from a gull’s view, the island is also leaching eruptive grit into the nearby ocean, discouraging regeneration of the rich kelp forests the eruption wiped out.

“It’s an amazing contrast between Kasatochi and anywhere else,” a University of Alaska Fairbanks diver and ecologist Steve Jewitt said at an onboard meeting in which scientists described what they found. “The kelp beds are not going to come back until you have some (rocks exposed). It should bounce back, but because of the (fine material yet to erode from the island into the ocean), it may take longer than we think.”

The two volcanologists on the island—Chris Nye of the Alaska Volcano Observatory and Willie Scott of Cascades Volcano Observatory—were interested in a unique white rock infused with long black crystals, which they infer came from deep under the crust and was spit from the heart of the volcano. During conversations in the ship’s galley, they also helped biologists understand what might have happened during the eruption, describing flows from the mouth of the volcano that may have deposited tens of feet of ash in a dramatic few hours. And, they observed that the superhot waves of gas and rock and grit must not have wiped out everything on the island.

“There’s plenty of the island that was never brought up to temperatures that would char organic stuff,” Nye said.

Scientists weren’t expecting to see much life on the island—and no biology is visible from a passing ship—but, while kneeling down in the mud, the researchers found living, growing organisms.

Spidery tendrils of green poked though the gray surface in areas, and after a few days plant specialists Steve and Sandra Talbot of Anchorage and Lars Walker of Nevada had found 19 living species, among them dune grass, lupine, and sea sandwort. Soils scientists Gary Michaelson of Palmer and Bronwen Wang of Anchorage dug up intact root wads under the blanket of erupted material. The roots seem to have somehow survived temperatures during the eruption that would boil water in your coffee cup (and also blow it to bits). The plant biologists think almost all the plants sprouted from the blanketed root mats the volcano’s heat did not kill.

Following their instinctual memories, crested and least auklets and other birds returned to the island at breeding time in June. Left behind are the scratches of their claws on the ground surface as they attempted in vain to find a place to lay eggs. Other than a few gulls, and a few other birds of random species, the island in August was silent except for the sound of the crashing surf.

“You don’t hear any birds right now,” Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge biologist Jeff Williams said while ankle-deep in mud on the island. “You should hear the songbirds—snow buntings, rosy finches, and winter wrens.”

Derek Sikes of the University of Alaska Museum of the North spent hours pressing his kneepads into Kasatochi’s surface to find a few insects alive on the island. Some probably wafted over from other islands (as close as 12 miles away), including a large blowfly, and many smaller flies under kelp washed up on the beach. Other insects farther inland somehow made it through a transformation so extreme that the only human artifact that survived was a blue kerosene container that was blasted out to sea and washed up later on the new Kasatochi beach (Tiglax crew members rescued it and a biologist used it on another island camp).

During his last day on the island, Sikes nosed into cracks between rocks of a former cliff face now again being exposed by erosion. On that reddish rock surface, he saw a dwarf spider and a stone centipede, two tiny creatures that somehow escaped oblivion as the island reset itself in geologic time.

So, it appears Kasatochi was not self-sterilized during a few August days in 2008. The smallest and luckiest of life forms clung to natural bunkers within the island, and mats of plant roots were buried quickly enough to withstand the heat of the eruption flows. Erosion and storms will beat down the plant life for years, and much time will pass before rock outcroppings emerge from the muck to become filled with bird life. But some day, perhaps 100 or 1,000 years from now, Kasatochi will again be the lush green island it was before August 7, 2008.