The recent history of a black rock

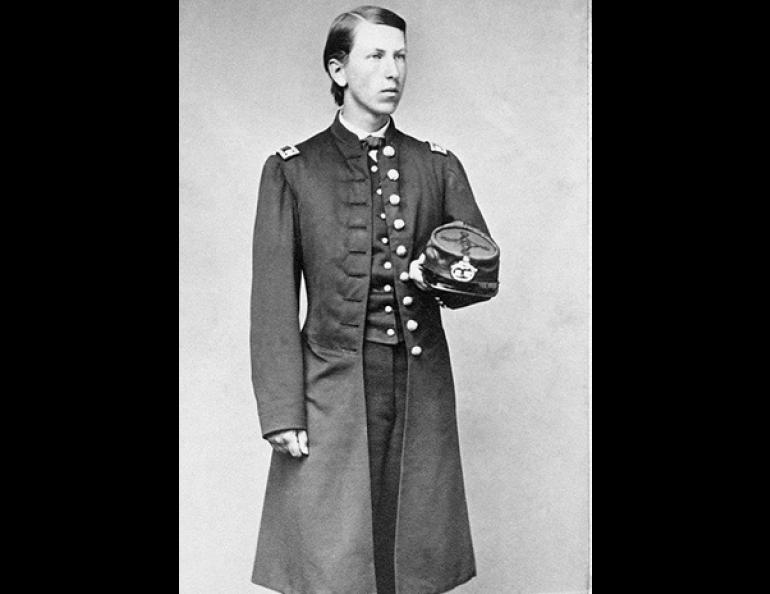

In June of 1867 — a few months before Alaska would become part of the United States with the transfer of $7.2 million to Russia — William Healey Dall picked up a shiny black rock from a riverbank.

Dall was near the mouth of the Nowitna River, which flows into the Yukon River between today’s villages of Tanana and Ruby.

He tucked away the interesting stone, scribbled a note about it in his journal, and continued on his expedition. His mission was to survey a possible route for a telegraph line along the Yukon River that might connect the U.S. with Europe via the Bering Strait.

One-hundred-fifty-seven years later, while recently visiting Washington, D.C., Jeff Rasic held that same piece of obsidian in his hand.

Rasic, an archaeologist and the science coordinator for all the 15 National Park Service units in Alaska, was at a gathering of colleagues in West Virginia. He had added a day to his trip from his home in Fairbanks to visit the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

There, he walked right to the institution’s geological collection to further explore one of his favorite projects: the sources of ancient obsidian tools found in Alaska.

Obsidian is a black, often translucent rock. Volcanic eruptions sometimes ooze out magma that turns into this natural glass as it cools.

Obsidian is hard, durable and can be worked to a razor-sharp edge. Archaeologists find it in sites all over Alaska where people once tipped spears, scraped hides and made knives with it. Far-north hunters also once implanted obsidian into the seats of their boats to draw whales to themselves.

“It’s a fluke-of-nature rock,” Rasic said. “Because it’s such a rare thing, we can make a very precise match between the artifact and its source.”

A good deal of the human-used obsidian in Alaska comes from a source called Batza Tena near the Indian River in Interior Alaska. There are a few other notable obsidian deposits, such as near Wiki Peak in the Wrangell Mountains, Okmok Caldera in the Aleutian Islands and sources in Southeast Alaska.

Rasic is always on the lookout for samples of Alaska obsidian. He wants to pinpoint long-forgotten sources and learn what the rocks can tell us about interactions between ancient Alaskans.

For example, he once linked an obsidian artifact from a 3,000-year-old site on Unalaska Island in the Aleutians to a source in the Wrangell Mountains, just a dozen miles from the Canada border.

“To find something (in the Aleutians) from Interior Alaska was a big surprise,” Rasic said.

How does Rasic tell the difference between Wiki Peak obsidian and obsidian from Okmok Volcano? He carries a hand-held machine that looks like a bar-code scanner.

In the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, Rasic pointed his machine at the black rock Dall had reported as a possible geological source. He pulled the trigger. The device sent out controlled beam of X-rays that excited electrons within the rock. That allowed Rasic to instantly know the concentration of elements in that piece of obsidian.

Dall’s rock was a perfect match to Batza Tena, which makes sense in that the source is 70 miles from the beach where Dall picked it up.

Rasic was pleasantly surprised to find that ancient people had worked this piece of obsidian, a rock he thought might have been from one of those unknown outcrops for which he is always searching.

Dall’s obsidian was “evidently from a nearby camp, carried there by people with connections to the Koyukuk River and the Batza Tena source,” Rasic said. “I was happy to have solved a piece of the puzzle, and also for the chance to overlap in a small way with this noted explorer.”

That naturalist and lover of Alaska left his name behind on more Alaska creatures and features than anyone else, including the Dall sheep and Dall’s porpoise.

His name also remains on Dall Glacier, Dall Point, Dall Island, Dall Lake, Dall Mountain, Dall Ridge, Dall River and Mount Dall.