A scientist’s view of Alaska, 150 years ago

One year before Alaska became part of America, 21-year old William Dall ascended the Yukon River on a sled, pulled by dogs. The man who left his name all over the state was in 1866 one of the first scientists to document the mysterious peninsula jutting toward Russia. He is probably the most thorough researcher to ever ponder this place.

On his first, three-year trip, Dall gathered more than 4,000 specimens from the hills and valleys of Alaska, from sea shells to great gray owls to a human skull. He sent them back by steamship to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., where he later processed them all.

Dall wrote his own summaries of Native people and their dialects, made weather and climate observations, and catalogued all the fish, birds, mammals and plants he saw. His “Alaska and its Resources” was published in 1870.

Dall came to Alaska as part of a mega-project that did not go as planned. The Western Union Company president wanted to stretch a telegraph line around the world. An unknown part of that span was through Alaska, then known as Russian America.

The telegraph line already existed from Washington, D.C. to Portland, and across 7,000 miles of Siberia. A man named Robert Kennicott’s job was to find the best terrain through Alaska to link with a 40-mile cable that would be laid on the ocean floor across Bering Strait.

Kennicott had heard of William Dall from a naturalist at Harvard, near where Dall grew up in Boston. Kennicott hired him on when Dall was 20. His title was director of the scientific corps of the Western Union Telegraph Expedition of 1865-1868.

Before Dall’s first Alaska exploration was complete, a cable was draped across the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, making the great northwestern route obsolete.

Dall, who took over for Kennicott after he died of a heart attack, received the news that his job had been terminated in a letter he received in the Yukon River village of Nulato. He read the letter one year after it was sent.

Dall had too much momentum to leave. He sent a letter back to Spencer Fullerton Baird of the Smithsonian Institution, who was sponsoring Dall’s sample gathering. Dall wrote Baird to say he was staying another year and hoped the Smithsonian could pay him the $200 they owed him and match that sum for the upcoming year. Baird knew a good deal when he saw one.

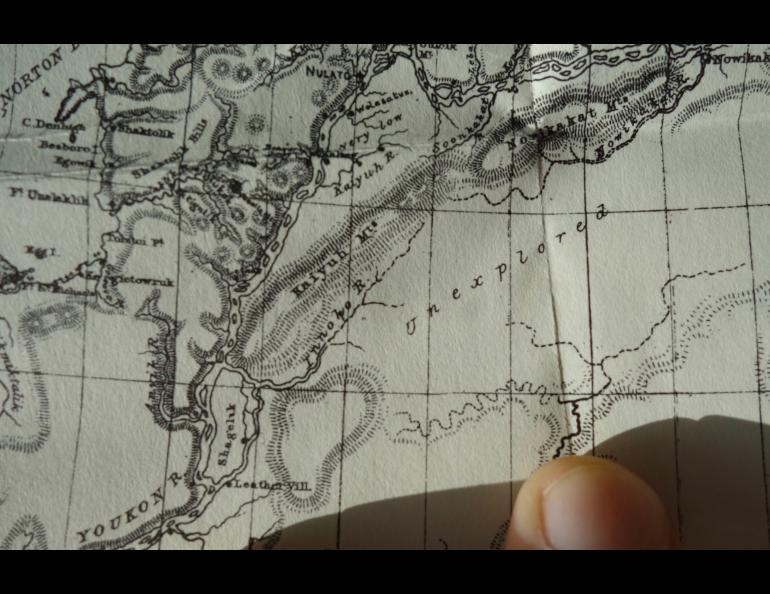

To illustrate his 628-page “Alaska and its Resources,” Dall sketched Natives, river landscapes, and different styles of sleds and snowshoes. He also drew plants, birds and a brand new map of Alaska.

The map is dark with detail in areas bordering the Yukon River (the length of which he descended in a canoe, probably the first white man to do so) and is blank north of the Brooks Range, and in most of the Interior between Fort Yukon and Cook Inlet. Despite poking more than 20,000 feet into the atmosphere, Denali is not on Dall’s map, being tucked far from any views available from the Yukon River.

Dall was not fond of the word Alaska. He thought it “a corruption, very far removed from the original word. When the early Russian traders first reached Unalaska, they were told by the natives that to the eastward was a great land or territory. This was called by the natives Al-ak-shak or Al-ay-ek-sa.”

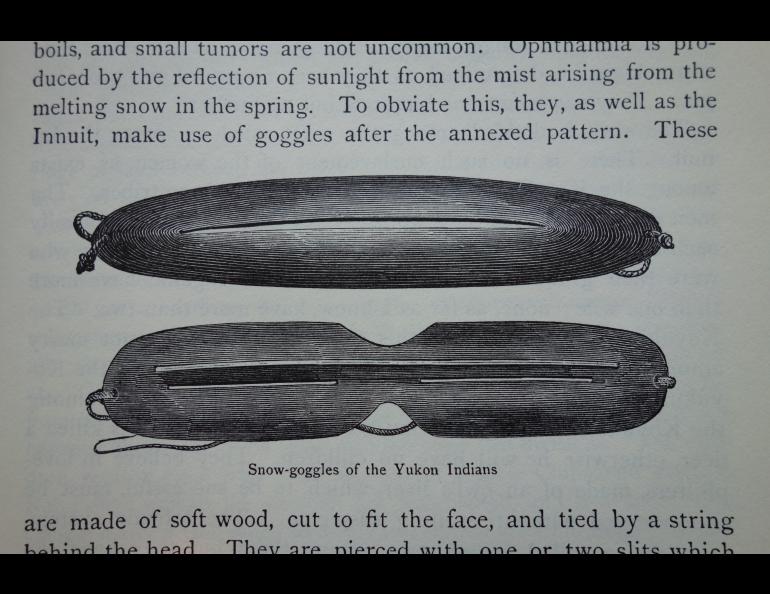

Dall was a world expert on shellfish, but he observed everything. As he was living and traveling with the original inhabitants, he described a year in the life of Native peoples of the central Yukon River.

“Life among the Indians is a constant struggle with nature, wrestling with hunger, cold and fatigue,” Dall wrote. “The victory is ever uncertain, and always hard-earned.”

March, Dall wrote, was a tough month for inland Natives, whose stores of salmon and other foods caught the year before were dwindling. Fresh food in March, if people were lucky, was fish from traps set in ice and grouse and snowshoe hares snared with loops of sinew.

Dall reported that some bands of Natives called April the “hunger month.” Things changed in May, when geese and ducks arrived by the millions, along with magnificent pulses of salmon.

Following three gritty years of discovery in Alaska, Dall left, boarding a steamer for San Francisco.

But he returned, again and again. He surveyed almost the entire 30,000-plus miles of the Alaska coast between 1871 to 1874. After marrying Annette Whitney in 1880, the couple steamed to Sitka for their honeymoon. On the way, they passed an unnamed island that Dall soon named Annette.

Dall probably knew more about Alaska than anyone, before his time or since. His contemporaries named the Dall’s porpoise and Dall’s sheep after him.

His name fills a whole column of Donald Orth’s Dictionary of Alaska Place Names. Alaskans might think of him when climbing Mount Dall, an 8,399-foot peak in Denali Park named in 1902 by government explorer Alfred Brooks.

Thanks to other explorers who followed him north and admired his work, William Dall is now spread over the Alaska map, from Dall Point at the mouth of the Yukon to Dall Island in extreme southeast Alaska, to Dall Glacier, Dall Lake, Dall River and Dall Ridge.