The sinking feeling over much of Alaska

To the delight of the local mosquitoes, Nicholas Hasson steps through a tangle of prickly spruce branches while wearing a backpack that holds a scientific instrument.

Hasson is walking as straight a line as he can through a Fairbanks subdivision built in the boreal forest. Hasson studies permafrost at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He is testing his equipment near a few homes not far from campus.

“We’re looking at the inside of the earth without cutting it open,” the graduate student says.

The device can produce images of what’s beneath the mossy surface using a process called electrical resistivity tomography. It is a bit complicated to explain, but Hasson says part of its magic are very-low-frequency radio waves that penetrate deep into the earth, broadcast from an antenna field in Hawaii.

Where Hasson now walks, people are noticing the appearance of sinkholes, like the one Hasson walks toward. That yawning hole, which opened near a landowner’s shed a few years ago, could swallow a truck if its driver veered off the nearby gravel road.

Hasson walks along the lip of the smelly-water-filled depression, known to scientists as a thermokarst. These craters in the forest are appearing in Interior Alaska due to warming air temperatures and possibly an increase in rainfall.

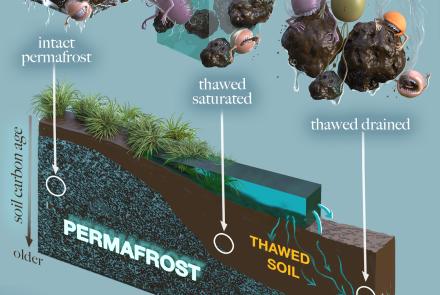

Defined as ground that has remained frozen through the heat of at least two summers, permafrost is a far-north phenomenon that is slowly disappearing under much — but not all — of northern Alaska. Permafrost is patchy beneath the landscape, mostly enduring in low-lying areas, on north-facing slopes and north of the Arctic Circle, where your shovel would clunk into frozen ground almost anywhere you stuck it.

Permafrost is a relic of colder times, when air temperatures were chilly enough to penetrate deep into the ground and freeze whatever was there. For many years, Alaska’s climate was cold enough preserve the solidity of the earth beneath the ground surface.

Thermokarst sinkholes develop due to the melting of a certain type of permafrost — huge chunks of ancient ice. Hasson calls the void they leave behind “ghost ice wedges.”

A visitor to the famous Permafrost Tunnel in nearby Fox sees intact walls of this glassy ice, the same type that that lurks beneath many forests, hills and lawns in northern Alaska. The massive ice formed thousands of years ago. It became entombed in the rolling hills of Alaska and Siberia when wind-blown soil blanketed the landscape.

With recent warming air temperatures, some Alaskans are noticing not only the occasional hole, but an overall sinking of the ground as water freed from permafrost drains away.

“We’re dropping in elevation because we live on ice cubes,” Hasson says, adding that parts of the Goldstream Valley north of Fairbanks have dropped nearly 15 feet since the 1960s.

The recent warmth of a few degrees over a few decades is subtle but significant. NOAA scientists recently changed their classification of the Fairbanks Airport meteorology station from “subarctic” to “warm summer continental,” because the average May temperature just went above 50 degrees F.

Because water is warmer than ice and percolates downward, it also helps to make permafrost disappear. Tom Douglas of the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory at nearby Fort Wainwright recently co-authored a paper on rainy years Fairbanks experienced in 2014 and 2016.

“In many places, the typical summer (permafrost) thaw has doubled or tripled what it has been in the past,” he said.

Though it lacks the climate drama of black spruce trees bursting into flames, thawing permafrost is a headache for those who live in structures on top of it and those who drive over roller-coaster roads. But permafrost holds an invisible threat that could affect everyone on Earth, Hasson says.

Thawing permafrost often emits methane, a greenhouse gas several times more potent at trapping heat than carbon dioxide (which also wafts from thawing permafrost, as does nitrous oxide).

How does that happen?

Frozen ground contains the stems and roots of plants buried in soil long ago. These specks and clumps that were swaying in the wind when mammoths roamed Interior Alaska are now becoming available to microorganisms that feed on them. Some of these microbes have themselves been suspended in frost for thousands of years.

“They are very hungry when they wake up,” Hasson says. “It’s a microbial feast — a carbon feast.”

Scientists have estimated that permafrost soils hold twice as much carbon as the concentration currently in our atmosphere, the 30-mile shell of gases surrounding the planet. How much of those stored gases will the awakened permafrost microbes release? That’s what scientists are trying to find out.

Hasson’s part in that equation is trying to map permafrost — a substance that lies beneath one quarter of all the land north of the Equator — by using the device attached to his backpack. He thinks recent advances have made it a tool of great promise in monitoring the slow-motion disaster happening over much of northern Alaska.